HOW and WHY TO SEARCH FOR YOUNG EINSTEINS

New research suggests new ways to nurture gifted children.

Every year in Singapore, 1% of pupils in the third year of primary school bring home an envelope headed “On government service”. Inside is an invitation to the city-state’s Gifted Education Programme. To receive the overture, pupils must ace maths, English and “general ability” tests. If their parents accept the offer, the children are taught using a special curriculum.

Singapore’s approach is emblematic of the traditional form of “gifted” education, which uses intelligence tests with strict thresholds to identify children with seemingly innate ability. Yet in many countries, it is being overhauled in two main ways. The first is that educationists use a broader range of methods to identify brilliant children, especially those from poor households. The second is an increasing focus on fostering the attitudes and personality traits found in successful people in various disciplines, including those who did not ace intelligence tests.

New research lies behind these shifts. It shows that countries which do not get the most from their best and brightest face considerable economic costs. The study also suggests that the nature-or-nurture debate is a false dichotomy. Intelligence is highly heritable and the best predictor of success. But it is far from the only characteristic that matters for future eminence.

IQ tests have attracted furious criticism. Christopher Hitchens argued, “There is…an unusually high and consistent correlation between the stupidity of a given person and [his] propensity to be impressed by the measurement of IQ.” Like any assessment, IQ tests are not perfect. However, researchers in cognitive science agree that general intelligence—not book-learning but the ability to reason, plan, solve problems, think abstractly, and so on—is an identifiable and essential attribute that IQ tests can measure.

Study of Mathematically Precocious Youth (SMPY). Founded 1971 over 25 years ago, it recruited 5,000 precocious children, each with intelligence-test scores in early adolescence high enough to enter university. Of the SMPY participants who scored among the top 0.5% for their age group in maths and verbal tests, 30% earned a doctorate, versus 1% of Americans. These children were also much more likely to have high incomes and to file patents. Of the top 0.01% of children, 50% went on to earn a PhD, medical or law degree.

Do gifted children go on to become disproportionately troubled? Of course, there are exceptions. However, on average, having a high IQ as a child is associated with better physical and mental health as an adult. Being moved up a school year tends to do them little harm.

Linking gifted education to economic growth is common sense in countries without many natural resources, such as Singapore. In 2013, two specialist maths schools were started in England. Sadly, however, the potential of poor bright children is often wasted. The likelihood of filing patents is still much greater among smart kids from wealthy families. A lot of talent is being squandered.

Gifted schemes have often not helped. When applications are voluntary, they come primarily from wealthy or pushy parents. 70% of pupils admitted to such programmes were white or Asian (only 30% of the school-age population).

It helps when schools test every child. Universal screening resulted in admissions increasing by 180% among poor children, 130% among Hispanics and 80% among black pupils. (Admissions among white children fell.) Miami-Dade has a lower IQ threshold for poor children or those for whom English is a second language, and 6.9% of black pupils are in the gifted programme, versus 2.4% and 3.6% in Florida and nationwide.

The “gifted” label has changed in favour of “high ability”. No state relies on a single IQ score to select students. School districts are also testing for other attributes, including spatial ability (i.e., the capacity to generate, manipulate and store visual images, which is strongly linked to achievement in science and technology later in life). Relying only on measures of intelligence will fail to find children with the potential to excel in adult life. Other possible paths to success may include passion, determination and creativity.

Whether termed “grit”, “task-motivation,” or “conscientiousness”, persistence is essential. “As much as talent counts, effort counts twice.” Deliberate practice over a long period (popularly understood as 10,000 hours) is critical. Talent requires development, and that should involve promoting hard work.

Children’s “mindset” (the beliefs they have about learning). Children who think they can change their intelligence have a growth mindset and quickly start to do better in tests. Teaching methods help. Interventions based on growth-mindset are less effective than their hype implies.

Gifted education should influence education more broadly. If primary-school pupils are taught using methods often reserved for brainier kids, fostering high expectations, complex problem-solving and cultivating meta-cognition (or “thinking about thinking”). Nearly every one of them went on to do much better on tests than their similar peers.

Roughly 50% of the variance in IQ scores is due to genetic differences. Nurture, hard work, and social background matter, but they undermine the idea that intelligence can be willed into being. As long as they are open to everyone, IQ tests still have a vital role to play. To find lost Einsteins, you have to look for them.

Reference:

1. “How and Why to Search For Young Einsteins” in the Mar 22nd, 2018 ECONOMIST

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

HOW TO SPOT A GENIUS

In an age of artificial intelligence, the human kind is increasingly important

Ervin Macic was despondent. While in school he twice won medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad and researched artificial intelligence, trying to speed up how models make predictions. He dreamed of one day joining an AI lab to make the technology safe. Yet the 19-year-old Bosnian prodigy was unable to take a place at the University of Oxford: its fees of £60,000 a year were five times his family’s annual income. So he went to the University of Sarajevo, where he sat programming exams on a decades-old computer.

Mr Macic’s case is far from unique. Around the world vast amounts of talent go to waste. Economists speak of “lost Einsteins” who might have produced transformative work had they been identified and nurtured. Nowhere are the consequences clearer than in AI, where the scarcity of top researchers allows a tiny cadre to command CEO-level pay. Governments that lavish billions on semiconductors to win the AI race neglect the talent that drives progress. Brains, treated with the same urgency as chips, could prove a better longer-term investment. What might an industrial policy for talent look like?

At present such policy amounts to procurement, not production. Governments focus on the last step: enticing existing superstars. The contest is fiercest between China and America. China’s Thousand Talents Plan, set up in 2008, aims to lure back citizens trained on elite foreign programmes; it will soon add a flexible K-visa to attract STEM specialists. America counters with the O-1A visa and EB-1A green card, both reserved for individuals of “extraordinary ability”. Other countries dabble. Japan has announced a $700m package to recruit top researchers. The EU’s “Choose Europe” scheme promises to make it a “magnet for researchers”.

A more extreme scarcity mindset about superstar talent drives the scramble among firms—and explains the premium placed on brains. As they race to build ever-larger models, individual researchers are seen as capable of unlocking breakthroughs worth billions. Sam Altman, boss of OpenAI, a superstar startup, once quipped about “10,000x engineer/researchers”, ultra-productive coders whose output can transform a field; the idea has since become industry lore. Elite researchers command valuations once reserved for companies.

These bidding wars rest on two assumptions. One is that a few elite researchers make outsize contributions; the other is that the supply of such talent is fixed. The first assumption is well founded. Breakthroughs are produced by a small cohort: the top 1% of researchers generate over a fifth of citations. James Watt’s refinements to the steam engine helped launch the Industrial Revolution. More recently, Katalin Karikó’s lonely pursuit of mRNA technology paved the way for covid-19 vaccines. Individuals shift the frontier for all.

The second assumption is less certain, however, for much potential never flowers. Geography is the first barrier. Some 90% of the world’s young live in developing countries, yet Nobel prizes overwhelmingly go to America, Europe and Japan. According to Paul Novosad of Dartmouth College and co-authors, the average laureate is born in the 95th percentile of global income. Although some disparity is to be expected, the scale suggests much talent does not have a chance to flourish. Similarly, Alex Bell of Georgia State University and co-authors find that American children from the richest 1% of households are ten times more likely to become inventors than those from below-median incomes. They estimate that closing America’s class, gender and race gaps in invention would quadruple the number of innovators, sharply raising the pace of discovery.

Where should governments begin their search for genius? One tempting answer is at the very top of the funnel, increasing the number of children who ever have a chance to develop their abilities. Universal fixes—improved nutrition, better schools, safer neighbourhoods—could help. But the problem is that, given how rare genius is even when better identified, such schemes are by their nature poorly targeted.

A more practical focus is the point at which talent first becomes visible: adolescence. By then stars can be spotted, even if many now slip away. Ruchir Agarwal of Harvard University and Patrick Gaule of the University of Bristol find that maths Olympiad contestants from poorer countries who score as highly as peers from rich ones go on to publish far less as adults, and are only half as likely to earn a doctorate from a leading university. Meanwhile, Philippe Aghion of the Collège de France and co-authors link Finnish conscription-test scores to patent data and find that shifting a high-ability teenager from a median to a high-income family would sharply raise their odds of later inventing something.

Sport shows the potential of systematic scouting. Baseball pioneered “farm systems” in the early 20th century, recruiting teenagers from small towns and developing them in lower-tier teams until they were ready for the big league. By the late 20th century, scouting had gone global. Last year the National Basketball Association featured a record 125 international players from over 40 countries—almost a quarter of the league—because of global academies. The result has been a surge in both the quality and diversity of athletes.

Some brilliance is obvious. Last year Gukesh Dommaraju, an Indian prodigy, became world chess champion at just 18, his rise nurtured by a thriving national chess scene. Earlier this year Hannah Cairo, a 17-year-old who grew up in the Bahamas, startled mathematicians by disproving the Mizohata-Takeuchi conjecture, a problem that had resisted solution for decades. Other promise can be identified at competitions such as the Olympiads, which are remarkably good predictors of future success. One in 40 winners of a gold medal at the International Mathematical Olympiad goes on to secure a big science prize, 50 times the rate of undergraduates at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (see chart). Guido van Rossum, a bronze medallist, created the Python programming language; half of OpenAI’s founders cut their teeth at Olympiads.

New opportunities for identification may also arise. AI, for instance, is creating markers of its own. A recent paper by Aaron Chatterji of OpenAI and co-authors suggests that a tenth of the world’s adults have now used ChatGPT, with nearly half of messages coming from those aged 25 or younger. Such digital traces could reveal patterns of originality or persistence. A systematic effort to embed scouts—in schools, competitions and even online—would widen the net, ensuring that gifted youngsters are discovered early.

Intelligently Designed

But finding geniuses is not just about discovery—it is also about development. Prodigies need mentors who can sharpen raw ability and open doors. John von Neumann, a Hungarian-born polymath, was tutored intensively in Budapest and later guided by Gabor Szego, a mathematician, who is said to have wept when the 15-year-old explained calculus back to him. Thankfully, mentors need not be geniuses themselves. Research by Ian Calaway of Stanford University, drawing on decades of maths-competition data, shows that when ordinary teachers run clubs and contests, exceptional students are far likelier to be spotted, to attend selective universities and to pursue research careers. In Zarzma, a Georgian town known for its monastery, Orthodox monks built a maths academy that now sends pupils to international junior Olympiads, blending rigorous teaching with close mentoring.

Prodigies also need access to clusters of high-ability peers. A study by Ufuk Akcigit of the University of Chicago, John Grigsby of Princeton University and Tom Nicholas of Harvard finds that America’s golden age of innovation was fuelled by migration: inventors left their home states in search of denser networks. Thomas Edison, born poor in rural Ohio, moved to New Jersey to build Menlo Park laboratory, where inventors could collaborate. In Tamil Nadu, India, chess has taken root so deeply that the state now produces grandmasters at a rate unmatched anywhere else in the country, thanks to local competition and coaching. Without access to stronger ecosystems, raw talent will struggle to flourish. As Tyler Cowen of George Mason University puts it: “You can’t just hire a driver in Togo, point out the window and say, ‘You’re an invisible genius.’ At the very least you have to get the Togo talent to Nigeria.”

Leading universities remain crucial gateways for talent, but their incentives are skewed. Scholarships for exceptional foreign students are scarce. In Britain, for instance, the University of Cambridge offers about 600 awards a year for over 24,000 international students. In America, only a handful of colleges—including Harvard, MIT, Princeton and Yale—are both need-blind and cover all costs for foreigners, and even at these only a few hundred international undergraduates receive substantial aid each year. At most others, international applicants are treated less as future innovators than as fee-payers. This has unfortunate consequences. Although two-thirds of Olympiad participants from poorer countries would like to study in America, only a quarter end up doing so. According to one estimate, easing immigration by removing financial barriers for such students would raise the scientific output of future cohorts by as much as 50%.

Governments have on occasion made efforts to identify and nurture talent, though rarely at scale. America’s Works Progress Administration, launched during the Depression, gave unemployed artists stipends, studios and performance venues, in effect serving as a scouting network. It supported figures such as Ralph Ellison, author of “Invisible Man”, and Jackson Pollock, an expressionist painter. Singapore has had more recent success grooming talent for its bureaucracy. National exams feed into a scholarship system run by the Public Service Commission, which sends students abroad to elite universities in exchange for years of civil-service work.

Yet today it is mostly philanthropists and charities that spot and cultivate stars. The Global Talent Fund, founded by Messrs Agarwal and Gaule, identifies Olympiad medalists from around the world and funds their studies at leading universities. Among its first cohort in 2024 was Mr Macic, the young Bosnian once stuck in Sarajevo. He is now studying maths and computer science at Oxford. Early results are notable. Imre Leader, a professor at Cambridge, tested his students with a puzzle—whether a triangle can be divided into smaller triangles, no two of the same size. Most of his best students wrestle with it for weeks; perhaps one manages to solve the problem each year. One of the fund’s first-years cracked it with a proof Mr Leader had never seen.

Other schemes take different approaches. Rise, backed by Schmidt Futures and the Rhodes Trust, runs a global competition for teenagers, selecting winners via project pitches and offering scholarships, mentoring and seed funding for ventures such as 3D-printed mind-controlled prosthetic arms. America’s Society for Science oversees the Regeneron Science Talent Search, the country’s most prestigious high-school science competition, which entices some 2,000 entrants each year to submit original research. Past finalists include Frank Wilczek and Sheldon Glashow, both Nobel-prizewinning physicists. Emergent Ventures, established in 2018 by Mr Cowen, offers small grants to gifted youngsters. “Money helps, but the real key is putting young talent with their peers,” says Mr Cowen. “In every field—painting, music, chess, AI—clusters are universal.”

These efforts are not particularly expensive. Governments could easily copy them—and on a much grander scale. Countries that mobilise talent tend to win strategic races. America’s scientific feats, from the Manhattan Project to Apollo, have often relied on deliberate recruitment of foreign scientists. Operation Paperclip alone brought in more than 1,500 German researchers in the 1940s and 1950s. Today, though, America’s ability to recruit is under pressure, as more young scientists head to Australia, Germany and the Gulf; President Donald Trump’s proposed $100,000 fee for a H-1B visa, on which many tech workers arrive, could make recruitment still more difficult. For its part, China is cultivating talent at scale. It now produces far more science graduates than America and a quarter of the world’s top AI researchers. However, it struggles to retain many of its brightest, who still look abroad for doctoral training and jobs.

The stakes are not only geopolitical. Removing barriers to the development of talent could multiply the global pool of innovators several times over. Unlocking such potential would speed the discovery of new medicines, hasten the green transition and propel AI. The result would be healthier, cleaner and more prosperous lives. Squandered talent is the world’s most neglected engine of progress. ■

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++CREATIVITY – SECRETS OF THE CREATIVE BRAIN

A leading neuroscientist who has spent decades studying creativity shares her research on where genius comes from, whether it is dependent on high IQ, and why it is so often accompanied by mental illness

As a psychiatrist and neuroscientist who studies creativity, I’ve had the pleasure of working with many gifted and high-profile subjects over the years, but Kurt Vonnegut—dear, funny, eccentric, lovable, tormented Kurt Vonnegut—will always be one of my favorites. Kurt was a faculty member at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop in the 1960s, and participated in the first big study I did as a member of the university’s psychiatry department. I was examining the anecdotal link between creativity and mental illness, and Kurt was an excellent case study.

He was intermittently depressed, but that was only the beginning. His mother had suffered from depression and committed suicide on Mother’s Day, when Kurt was 21 and home on military leave during World War II. His son, Mark, was originally diagnosed with schizophrenia but may actually have bipolar disorder. (Mark, who is a practicing physician, recounts his experiences in two books, The Eden Express and Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So, in which he reveals that many family members struggled with psychiatric problems. “My mother, my cousins, and my sisters weren’t doing so great,” he writes. “We had eating disorders, co-dependency, outstanding warrants, drug and alcohol problems, dating and employment problems, and other ‘issues.’ ”)

While mental illness clearly runs in the Vonnegut family, so, I found, does creativity. Kurt’s father was a gifted architect, and his older brother Bernard was a talented physical chemist and inventor who possessed 28 patents. Mark is a writer, and both of Kurt’s daughters are visual artists. Kurt’s work, of course, needs no introduction.

For many of my subjects from that first study—all writers associated with the Iowa Writers’ Workshop—mental illness and creativity went hand in hand. This link is not surprising. The archetype of the mad genius dates back to at least classical times, when Aristotle noted, “Those who have been eminent in philosophy, politics, poetry, and the arts have all had tendencies toward melancholia.” This pattern is a recurring theme in Shakespeare’s plays, such as when Theseus, in A Midsummer Night’s Dream, observes, “The lunatic, the lover, and the poet / Are of imagination all compact.” John Dryden made a similar point in a heroic couplet: “Great wits are sure to madness near allied, / And thin partitions do their bounds divide.”

Compared with many of history’s creative luminaries, Vonnegut, who died of natural causes, got off relatively easy. Among those who ended up losing their battles with mental illness through suicide are Virginia Woolf, Ernest Hemingway, Vincent van Gogh, John Berryman, Hart Crane, Mark Rothko, Diane Arbus, Anne Sexton, and Arshile Gorky.

My interest in this pattern is rooted in my dual identities as a scientist and a literary scholar. In an early parallel with Sylvia Plath, a writer I admired, I studied literature at Radcliffe and then went to Oxford on a Fulbright scholarship; she studied literature at Smith and attended Cambridge on a Fulbright. Then our paths diverged, and she joined the tragic list above. My curiosity about our different outcomes has shaped my career. I earned a doctorate in literature in 1963 and joined the faculty of the University of Iowa to teach Renaissance literature. At the time, I was the first woman the university’s English department had ever hired into a tenure-track position, and so I was careful to publish under the gender-neutral name of N. J. C. Andreasen.

Not long after this, a book I’d written about the poet John Donne was accepted for publication by Princeton University Press. Instead of feeling elated, I felt almost ashamed and self-indulgent. Who would this book help? What if I channeled the effort and energy I’d invested in it into a career that might save people’s lives? Within a month, I made the decision to become a research scientist, perhaps a medical doctor. I entered the University of Iowa’s medical school, in a class that included only five other women, and began working with patients suffering from schizophrenia and mood disorders. I was drawn to psychiatry because at its core is the most interesting and complex organ in the human body: the brain.

I have spent much of my career focusing on the neuroscience of mental illness, but in recent decades I’ve also focused on what we might call the science of genius, trying to discern what combination of elements tends to produce particularly creative brains. What, in short, is the essence of creativity? Over the course of my life, I’ve kept coming back to two more-specific questions: What differences in nature and nurture can explain why some people suffer from mental illness and some do not? And why are so many of the world’s most creative minds among the most afflicted? My latest study, for which I’ve been scanning the brains of some of today’s most illustrious scientists, mathematicians, artists, and writers, has come closer to answering this second question than any other research to date.

The first attempted examinations of the connection between genius and insanity were largely anecdotal. In his 1891 book, The Man of Genius, Cesare Lombroso, an Italian physician, provided a gossipy and expansive account of traits associated with genius—left-handedness, celibacy, stammering, precocity, and, of course, neurosis and psychosis—and he linked them to many creative individuals, including Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Sir Isaac Newton, Arthur Schopenhauer, Jonathan Swift, Charles Darwin, Lord Byron, Charles Baudelaire, and Robert Schumann. Lombroso speculated on various causes of lunacy and genius, ranging from heredity to urbanization to climate to the phases of the moon. He proposed a close association between genius and degeneracy and argued that both are hereditary.

Francis Galton, a cousin of Charles Darwin, took a much more rigorous approach to the topic. In his 1869 book, Hereditary Genius, Galton used careful documentation—including detailed family trees showing the more than 20 eminent musicians among the Bachs, the three eminent writers among the Brontës, and so on—to demonstrate that genius appears to have a strong genetic component. He was also the first to explore in depth the relative contributions of nature and nurture to the development of genius.

As research methodology improved over time, the idea that genius might be hereditary gained support. For his 1904 Study of British Genius, the English physician Havelock Ellis twice reviewed the 66 volumes of The Dictionary of National Biography. In his first review, he identified individuals whose entries were three pages or longer. In his second review, he eliminated those who “displayed no high intellectual ability” and added those who had shorter entries but showed evidence of “intellectual ability of high order.” His final list consisted of 1,030 individuals, only 55 of whom were women. Much like Lombroso, he examined how heredity, general health, social class, and other factors may have contributed to his subjects’ intellectual distinction. Although Ellis’s approach was resourceful, his sample was limited, in that the subjects were relatively famous but not necessarily highly creative. He found that 8.2 percent of his overall sample of 1,030 suffered from melancholy and 4.2 percent from insanity. Because he was relying on historical data provided by the authors of The Dictionary of National Biography rather than direct contact, his numbers likely underestimated the prevalence of mental illness in his sample.

A more empirical approach can be found in the early-20th-century work of Lewis M. Terman, a Stanford psychologist whose multivolume Genetic Studies of Genius is one of the most legendary studies in American psychology. He used a longitudinal design—meaning he studied his subjects repeatedly over time—which was novel then, and the project eventually became the longest-running longitudinal study in the world. Terman himself had been a gifted child, and his interest in the study of genius derived from personal experience. (Within six months of starting school, at age 5, Terman was advanced to third grade—which was not seen at the time as a good thing; the prevailing belief was that precocity was abnormal and would produce problems in adulthood.) Terman also hoped to improve the measurement of “genius” and test Lombroso’s suggestion that it was associated with degeneracy.

In 1916, as a member of the psychology department at Stanford, Terman developed America’s first IQ test, drawing from a version developed by the French psychologist Alfred Binet. This test, known as the Stanford-Binet Intelligence Scales, contributed to the development of the Army Alpha, an exam the American military used during World War I to screen recruits and evaluate them for work assignments and determine whether they were worthy of officer status.

Terman eventually used the Stanford-Binet test to select high-IQ students for his longitudinal study, which began in 1921. His long-term goal was to recruit at least 1,000 students from grades three through eight who represented the smartest 1 percent of the urban California population in that age group. The subjects had to have an IQ greater than 135, as measured by the Stanford-Binet test. The recruitment process was intensive: students were first nominated by teachers, then given group tests, and finally subjected to individual Stanford-Binet tests. After various enrichments—adding some of the subjects’ siblings, for example—the final sample consisted of 856 boys and 672 girls. One finding that emerged quickly was that being the youngest student in a grade was an excellent predictor of having a high IQ. (This is worth bearing in mind today, when parents sometimes choose to hold back their children precisely so they will not be the youngest in their grades.)

These children were initially evaluated in all sorts of ways. Researchers took their early developmental histories, documented their play interests, administered medical examinations—including 37 different anthropometric measurements—and recorded how many books they’d read during the past two months, as well as the number of books available in their homes (the latter number ranged from zero to 6,000, with a mean of 328). These gifted children were then reevaluated at regular intervals throughout their lives.

“The Termites,” as Terman’s subjects have come to be known, have debunked some stereotypes and introduced new paradoxes. For example, they were generally physically superior to a comparison group—taller, healthier, more athletic. Myopia (no surprise) was the only physical deficit. They were also more socially mature and generally better adjusted. And these positive patterns persisted as the children grew into adulthood. They tended to have happy marriages and high salaries. So much for the concept of “early ripe and early rotten,” a common assumption when Terman was growing up.

But despite the implications of the title Genetic Studies of Genius, the Termites’ high IQs did not predict high levels of creative achievement later in life. Only a few made significant creative contributions to society; none appear to have demonstrated extremely high creativity levels of the sort recognized by major awards, such as the Nobel Prize. (Interestingly, William Shockley, who was a 12-year-old Palo Alto resident in 1922, somehow failed to make the cut for the study, even though he would go on to share a Nobel Prize in physics for the invention of the transistor.) Thirty percent of the men and 33 percent of the women did not even graduate from college. A surprising number of subjects pursued humble occupations, such as semiskilled trades or clerical positions. As the study evolved over the years, the term gifted was substituted for genius. Although many people continue to equate intelligence with genius, a crucial conclusion from Terman’s study is that having a high IQ is not equivalent to being highly creative. Subsequent studies by other researchers have reinforced Terman’s conclusions, leading to what’s known as the threshold theory, which holds that above a certain level, intelligence doesn’t have much effect on creativity: most creative people are pretty smart, but they don’t have to be that smart, at least as measured by conventional intelligence tests. An IQ of 120, indicating that someone is very smart but not exceptionally so, is generally considered sufficient for creative genius.

But if high IQ does not indicate creative genius, then what does? And how can one identify creative people for a study?

One approach, which is sometimes referred to as the study of “little c,” is to develop quantitative assessments of creativity—a necessarily controversial task, given that it requires settling on what creativity actually is. The basic concept that has been used in the development of these tests is skill in “divergent thinking,” or the ability to come up with many responses to carefully selected questions or probes, as contrasted with “convergent thinking,” or the ability to come up with the correct answer to problems that have only one answer. For example, subjects might be asked, “How many uses can you think of for a brick?” A person skilled in divergent thinking might come up with many varied responses, such as building a wall; edging a garden; and serving as a bludgeoning weapon, a makeshift shot put, a bookend. Like IQ tests, these exams can be administered to large groups of people. Assuming that creativity is a trait everyone has in varying amounts, those with the highest scores can be classified as exceptionally creative and selected for further study.

While this approach is quantitative and relatively objective, its weakness is that certain assumptions must be accepted: that divergent thinking is the essence of creativity, that creativity can be measured using tests, and that high-scoring individuals are highly creative people. One might argue that some of humanity’s most creative achievements have been the result of convergent thinking—a process that led to Newton’s recognition of the physical formulae underlying gravity, and Einstein’s recognition that E=mc2.

A second approach to defining creativity is the “duck test”: if it walks like a duck and quacks like a duck, it must be a duck. This approach usually involves selecting a group of people—writers, visual artists, musicians, inventors, business innovators, scientists—who have been recognized for some kind of creative achievement, usually through the awarding of major prizes (the Nobel, the Pulitzer, and so forth). Because this approach focuses on people whose widely recognized creativity sets them apart from the general population, it is sometimes referred to as the study of “big C.” The problem with this approach is its inherent subjectivity. What does it mean, for example, to have “created” something? Can creativity in the arts be equated with creativity in the sciences or in business, or should such groups be studied separately? For that matter, should science or business innovation be considered creative at all?

Although I recognize and respect the value of studying “little c,” I am an unashamed advocate of studying “big C.” I first used this approach in the mid-1970s and 1980s, when I conducted one of the first empirical studies of creativity and mental illness. Not long after I joined the psychiatry faculty of the Iowa College of Medicine, I ran into the chair of the department, a biologically oriented psychiatrist known for his salty language and male chauvinism. “Andreasen,” he told me, “you may be an M.D./Ph.D., but that Ph.D. of yours isn’t worth sh–, and it won’t count favorably toward your promotion.” I was proud of my literary background and believed that it made me a better clinician and a better scientist, so I decided to prove him wrong by using my background as an entry point to a scientific study of genius and insanity.

The University of Iowa is home to the Writers’ Workshop, the oldest and most famous creative-writing program in the United States (UNESCO has designated Iowa City as one of its seven “Cities of Literature,” along with the likes of Dublin and Edinburgh). Thanks to my time in the university’s English department, I was able to recruit study subjects from the workshop’s ranks of distinguished permanent and visiting faculty. Over the course of 15 years, I studied not only Kurt Vonnegut but Richard Yates, John Cheever, and 27 other well-known writers.

Going into the study, I keyed my hypotheses off the litany of famous people who I knew had personal or family histories of mental illness. James Joyce, for example, had a daughter who suffered from schizophrenia, and he himself had traits that placed him on the schizophrenia spectrum. (He was socially aloof and even cruel to those close to him, and his writing became progressively more detached from his audience and from reality, culminating in the near-psychotic neologisms and loose associations of Finnegans Wake.) Bertrand Russell, a philosopher whose work I admired, had multiple family members who suffered from schizophrenia. Einstein had a son with schizophrenia, and he himself displayed some of the social and interpersonal ineptitudes that can characterize the illness. Based on these clues, I hypothesized that my subjects would have an increased rate of schizophrenia in family members but that they themselves would be relatively well. I also hypothesized that creativity might run in families, based on prevailing views that the tendencies toward psychosis and toward having creative and original ideas were closely linked.

I began by designing a standard interview for my subjects, covering topics such as developmental, social, family, and psychiatric history, and work habits and approach to writing. Drawing on creativity studies done by the psychiatric epidemiologist Thomas McNeil, I evaluated creativity in family members by assigning those who had had very successful creative careers an A++ rating and those who had pursued creative interests or hobbies an A+.

My final challenge was selecting a control group. After entertaining the possibility of choosing a homogeneous group whose work is not usually considered creative, such as lawyers, I decided that it would be best to examine a more varied group of people from a mixture of professions, such as administrators, accountants, and social workers. I matched this control group with the writers according to age and educational level. By matching based on education, I hoped to match for IQ, which worked out well; both the test and the control groups had an average IQ of about 120. These results confirmed Terman’s findings that creative genius is not the same as high IQ. If having a very high IQ was not what made these writers creative, then what was?

While my workshop study answered some questions, it raised others. Why does creativity run in families? What is it that gets transmitted? How much is due to nature and how much to nurture? Are writers especially prone to mood disorders because writing is an inherently lonely and introspective activity? What would I find if I studied a group of scientists instead?

These questions percolated in my mind in the weeks, months, and eventually years after the study. As I focused my research on the neurobiology of severe mental illnesses, including schizophrenia and mood disorders, studying the nature of creativity—important as the topic was and is—seemed less pressing than searching for ways to alleviate the suffering of patients stricken with these dreadful and potentially lethal brain disorders. During the 1980s, new neuroimaging techniques gave researchers the ability to study patients’ brains directly, an approach I began using to answer questions about how and why the structure and functional activity of the brain is disrupted in some people with serious mental illnesses.

As I spent more time with neuroimaging technology, I couldn’t help but wonder what we would find if we used it to look inside the heads of highly creative people. Would we see a little genie that doesn’t exist inside other people’s heads?

Today’s neuroimaging tools show brain structure with a precision approximating that of the examination of post-mortem tissue; this allows researchers to study all sorts of connections between brain measurements and personal characteristics. For example, we know that London taxi drivers, who must memorize maps of the city to earn a hackney’s license, have an enlarged hippocampus—a key memory region—as demonstrated in a magnetic-resonance-imaging, or MRI, study. (They know it, too: on a recent trip to London, I was proudly regaled with this information by several different taxi drivers.) Imaging studies of symphony-orchestra musicians have found them to possess an unusually large Broca’s area—a part of the brain in the left hemisphere that is associated with language—along with other discrepancies. Using another technique, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI), we can watch how the brain behaves when engaged in thought.

Designing neuroimaging studies, however, is exceedingly tricky. Capturing human mental processes can be like capturing quicksilver. The brain has as many neurons as there are stars in the Milky Way, each connected to other neurons by billions of spines, which contain synapses that change continuously depending on what the neurons have recently learned. Capturing brain activity using imaging technology inevitably leads to oversimplifications, as sometimes evidenced by news reports that an investigator has found the location of something—love, guilt, decision making—in a single region of the brain.

And what are we even looking for when we search for evidence of “creativity” in the brain? Although we have a definition of creativity that many people accept—the ability to produce something that is novel or original and useful or adaptive—achieving that “something” is part of a complex process, one often depicted as an “aha” or “eureka” experience. This narrative is appealing—for example, “Newton developed the concept of gravity around 1666, when an apple fell on his head while he was meditating under an apple tree.” The truth is that by 1666, Newton had already spent many years teaching himself the mathematics of his time (Euclidean geometry, algebra, Cartesian coordinates) and inventing calculus so that he could measure planetary orbits and the area under a curve. He continued to work on his theory of gravity over the subsequent years, completing the effort only in 1687, when he published Philosophiœ Naturalis Principia Mathematica. In other words, Newton’s formulation of the concept of gravity took more than 20 years and included multiple components: preparation, incubation, inspiration—a version of the eureka experience—and production. Many forms of creativity, from writing a novel to discovering the structure of DNA, require this kind of ongoing, iterative process.

With functional magnetic resonance imaging, the best we can do is capture brain activity during brief moments in time while subjects are performing some task. For instance, observing brain activity while test subjects look at photographs of their relatives can help answer the question of which parts of the brain people use when they recognize familiar faces. Creativity, of course, cannot be distilled into a single mental process, and it cannot be captured in a snapshot—nor can people produce a creative insight or thought on demand. I spent many years thinking about how to design an imaging study that could identify the unique features of the creative brain.

Most of the human brain’s high-level functions arise from the six layers of nerve cells and their dendrites embedded in its enormous surface area, called the cerebral cortex, which is compressed to a size small enough to be carried around on our shoulders through a process known as gyrification—essentially, producing lots of folds. Some regions of the brain are highly specialized, receiving sensory information from our eyes, ears, skin, mouth, or nose, or controlling our movements. We call these regions the primary visual, auditory, sensory, and motor cortices. They collect information from the world around us and execute our actions. But we would be helpless, and effectively nonhuman, if our brains consisted only of these regions.

In fact, the most extensively developed regions in the human brain are known as association cortices. These regions help us interpret and make use of the specialized information collected by the primary visual, auditory, sensory, and motor regions. For example, as you read these words on a page or a screen, they register as black lines on a white background in your primary visual cortex. If the process stopped at that point, you wouldn’t be reading at all. To read, your brain, through miraculously complex processes that scientists are still figuring out, needs to forward those black letters on to association-cortex regions such as the angular gyrus, so that meaning is attached to them; and then on to language-association regions in the temporal lobes, so that the words are connected not only to one another but also to their associated memories and given richer meanings. These associated memories and meanings constitute a “verbal lexicon,” which can be accessed for reading, speaking, listening, and writing. Each person’s lexicon is a bit different, even if the words themselves are the same, because each person has different associated memories and meanings. One difference between a great writer like Shakespeare and, say, the typical stockbroker is the size and richness of the verbal lexicon in his or her temporal association cortices, as well as the complexity of the cortices’ connections with other association regions in the frontal and parietal lobes.

A neuroimaging study I conducted in 1995 using positron-emission tomography, or PET, scanning turned out to be unexpectedly useful in advancing my own understanding of association cortices and their role in the creative process.

This PET study was designed to examine the brain’s different memory systems, which the great Canadian psychologist Endel Tulving identified. One system, episodic memory, is autobiographical—it consists of information linked to an individual’s personal experiences. It is called “episodic” because it consists of time-linked sequential information, such as the events that occurred on a person’s wedding day. My team and I compared this with another system, that of semantic memory, which is a repository of general information and is not personal or time-linked. In this study, we divided episodic memory into two subtypes. We examined focused episodic memory by asking subjects to recall a specific event that had occurred in the past and to describe it with their eyes closed. And we examined a condition that we called random episodic silent thought, or REST: we asked subjects to lie quietly with their eyes closed, to relax, and to think about whatever came to mind. In essence, they would be engaged in “free association,” letting their minds wander. The acronym REST was intentionally ironic; we suspected that the association regions of the brain would actually be wildly active during this state.

This suspicion was based on what we had learned about free association from the psychoanalytic approach to understanding the mind. In the hands of Freud and other psychoanalysts, free association—spontaneously saying whatever comes to mind without censorship—became a window into understanding unconscious processes. Based on my interviews with the creative subjects in my workshop study, and from additional conversations with artists, I knew that such unconscious processes are an important component of creativity. For example, Neil Simon told me: “I don’t write consciously—it is as if the muse sits on my shoulder” and “I slip into a state that is apart from reality.” (Examples from history suggest the same thing. Samuel Taylor Coleridge once described how he composed an entire 300-line poem about Kubla Khan while in an opiate-induced, dreamlike state, and began writing it down when he awoke; he said he then lost most of it when he got interrupted and called away on an errand—thus the finished poem he published was but a fragment of what originally came to him in his dreamlike state.)

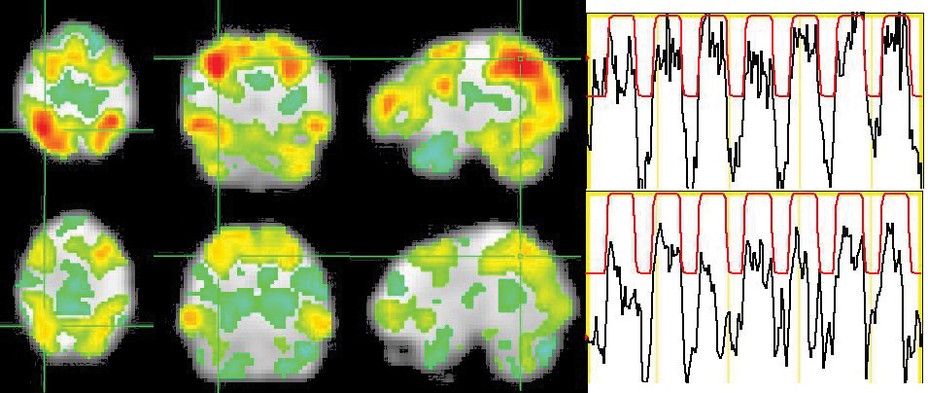

Based on all this, I surmised that observing which parts of the brain are most active during free association would give us clues about the neural basis of creativity. And what did we find? Sure enough, the association cortices were wildly active during REST.

I realized that I obviously couldn’t capture the entire creative process—instead, I could home in on the parts of the brain that make creativity possible. Once I arrived at this idea, the design for the imaging studies was obvious: I needed to compare the brains of highly creative people with those of control subjects as they engaged in tasks that activated their association cortices.

For years, I had been asking myself what might be special or unique about the brains of the workshop writers I had studied. In my own version of a eureka moment, the answer finally came to me: creative people are better at recognizing relationships, making associations and connections, and seeing things in an original way—seeing things that others cannot see. To test this capacity, I needed to study the regions of the brain that go crazy when you let your thoughts wander. I needed to target the association cortices. In addition to REST, I could observe people performing simple tasks that are easy to do in an MRI scanner, such as word association, which would permit me to compare highly creative people—who have that “genie in the brain”—with the members of a control group matched by age and education and gender, people who have “ordinary creativity” and who have not achieved the levels of recognition that characterize highly creative people. I was ready to design Creativity Study II.

This time around, I wanted to examine a more diverse sample of creativity, from the sciences as well as the arts. My motivations were partly selfish—I wanted the chance to discuss the creative process with people who might think and work differently, and I thought I could probably learn a lot by listening to just a few people from specific scientific fields. After all, each would be an individual jewel—a fascinating study on his or her own. Now that I’m about halfway through the study, I can say that this is exactly what has happened. My individual jewels so far include, among others, the filmmaker George Lucas, the mathematician and Fields Medalist William Thurston, the Pulitzer Prize–winning novelist Jane Smiley, and six Nobel laureates from the fields of chemistry, physics, and physiology or medicine. Because winners of major awards are typically older, and because I wanted to include some younger people, I’ve also recruited winners of the National Institutes of Health Pioneer Award and other prizes in the arts.

Apart from stating their names, I do not have permission to reveal individual information about my subjects. And because the study is ongoing (each subject can take as long as a year to recruit, making for slow progress), we do not yet have any definitive results—though we do have a good sense of the direction that things are taking. By studying the structural and functional characteristics of subjects’ brains in addition to their personal and family histories, we are learning an enormous amount about how creativity occurs in the brain, as well as whether these scientists and artists display the same personal or familial connections to mental illness that the subjects in my Iowa Writers’ Workshop study did.

To participate in the study, each subject spends three days in Iowa City, since it is important to conduct the research using the same MRI scanner. The subjects and I typically get to know each other over dinner at my home (and a bottle of Bordeaux from my cellar), and by prowling my 40-acre nature retreat in an all-terrain vehicle, observing whatever wildlife happens to be wandering around. Relaxing together and getting a sense of each other’s human side is helpful going into the day and a half of brain scans and challenging conversations that will follow.

We begin the actual study with an MRI scan, during which subjects perform three different tasks, in addition to REST: word association, picture association, and pattern recognition. Each experimental task alternates with a control task; during word association, for example, subjects are shown words on a screen and asked to either think of the first word that comes to mind (the experimental task) or silently repeat the word they see (the control task). Speaking disrupts the scanning process, so subjects silently indicate when they have completed a task by pressing a button on a keypad.

Playing word games inside a thumping, screeching hollow tube seems like a far cry from the kind of meandering, spontaneous discovery process that we tend to associate with creativity. It is, however, as close as one can come to a proxy for that experience, apart from REST. You cannot force creativity to happen—every creative person can attest to that. But the essence of creativity is making connections and solving puzzles. The design of these MRI tasks permits us to visualize what is happening in the creative brain when it’s doing those things.

As I hypothesized, the creative people have shown stronger activations in their association cortices during all four tasks than the controls have. (See the images on page 74.) This pattern has held true for both the artists and the scientists, suggesting that similar brain processes may underlie a broad spectrum of creative expression. Common stereotypes about “right brained” versus “left brained” people notwithstanding, this parallel makes sense. Many creative people are polymaths, people with broad interests in many fields—a common trait among my study subjects.

After the brain scans, I settle in with subjects for an in-depth interview. Preparing for these interviews can be fun (rewatching all of George Lucas’s films, for example, or reading Jane Smiley’s collected works) as well as challenging (toughing through mathematics papers by William Thurston). I begin by asking subjects about their life history—where they grew up, where they went to school, what activities they enjoyed. I ask about their parents—their education, occupation, and parenting style—and about how the family got along. I learn about brothers, sisters, and children, and get a sense for who else in a subject’s family is or has been creative and how creativity may have been nurtured at home. We talk about how the subjects managed the challenges of growing up, any early interests and hobbies (particularly those related to the creative activities they pursue as adults), dating patterns, life in college and graduate school, marriages, and child-rearing. I ask them to describe a typical day at work and to think through how they have achieved such a high level of creativity. (One thing I’ve learned from this line of questioning is that creative people work much harder than the average person—and usually that’s because they love their work.)

One of the most personal and sometimes painful parts of the interview is when I ask about mental illness in subjects’ families as well as in their own lives. They’ve told me about such childhood experiences as having a mother commit suicide or watching ugly outbreaks of violence between two alcoholic parents, and the pain and scars that these experiences have inflicted. (Two of the 13 creative subjects in my current study have lost a parent to suicide—a rate many times that of the general U.S. population.) Talking with those subjects who have suffered from a mental illness themselves, I hear about how it has affected their work and how they have learned to cope.

So far, this study—which has examined 13 creative geniuses and 13 controls—has borne out a link between mental illness and creativity similar to the one I found in my Writers’ Workshop study. The creative subjects and their relatives have a higher rate of mental illness than the controls and their relatives do (though not as high a rate as I found in the first study), with the frequency being fairly even across the artists and the scientists. The most-common diagnoses include bipolar disorder, depression, anxiety or panic disorder, and alcoholism. I’ve also found some evidence supporting my early hypothesis that exceptionally creative people are more likely than control subjects to have one or more first-degree relatives with schizophrenia. Interestingly, when the physician and researcher Jon L. Karlsson examined the relatives of everyone listed in Iceland’s version of Who’s Who in the 1940s and ’60s, he found that they had higher-than-average rates of schizophrenia. Leonard Heston, a former psychiatric colleague of mine at Iowa, conducted an influential study of the children of schizophrenic mothers raised from infancy by foster or adoptive parents, and found that more than 10 percent of these children developed schizophrenia, as compared with zero percent of a control group. This suggests a powerful genetic component to schizophrenia. Heston and I discussed whether some particularly creative people owe their gifts to a subclinical variant of schizophrenia that loosens their associative links sufficiently to enhance their creativity but not enough to make them mentally ill.

As in the first study, I’ve also found that creativity tends to run in families, and to take diverse forms. In this arena, nurture clearly plays a strong role. Half the subjects come from very high-achieving backgrounds, with at least one parent who has a doctoral degree. The majority grew up in an environment where learning and education were highly valued. This is how one person described his childhood:

Our family evenings—just everybody sitting around working. We’d all be in the same room, and [my mother] would be working on her papers, preparing her lesson plans, and my father had huge stacks of papers and journals … This was before laptops, and so it was all paper-based. And I’d be sitting there with my homework, and my sisters are reading. And we’d just spend a few hours every night for 10 to 15 years—that’s how it was. Just working together. No TV.

So why do these highly gifted people experience mental illness at a higher-than-average rate? Given that (as a group) their family members have higher rates than those that occur in the general population or in the matched comparison group, we must suspect that nature plays a role—that Francis Galton and others were right about the role of hereditary factors in people’s predisposition to both creativity and mental illness. We can only speculate about what those factors might be, but there are some clues in how these people describe themselves and their lifestyles.

One possible contributory factor is a personality style shared by many of my creative subjects. These subjects are adventuresome and exploratory. They take risks. Particularly in science, the best work tends to occur in new frontiers. (As a popular saying among scientists goes: “When you work at the cutting edge, you are likely to bleed.”) They have to confront doubt and rejection. And yet they have to persist in spite of that, because they believe strongly in the value of what they do. This can lead to psychic pain, which may manifest itself as depression or anxiety, or lead people to attempt to reduce their discomfort by turning to pain relievers such as alcohol.

I’ve been struck by how many of these people refer to their most creative ideas as “obvious.” Since these ideas are almost always the opposite of obvious to other people, creative luminaries can face doubt and resistance when advocating for them. As one artist told me, “The funny thing about [one’s own] talent is that you are blind to it. You just can’t see what it is when you have it … When you have talent and see things in a particular way, you are amazed that other people can’t see it.” Persisting in the face of doubt or rejection, for artists or for scientists, can be a lonely path—one that may also partially explain why some of these people experience mental illness.

One interesting paradox that has emerged during conversations with subjects about their creative processes is that, though many of them suffer from mood and anxiety disorders, they associate their gifts with strong feelings of joy and excitement. “Doing good science is simply the most pleasurable thing anyone can do,” one scientist told me. “It is like having good sex. It excites you all over and makes you feel as if you are all-powerful and complete.” This is reminiscent of what creative geniuses throughout history have said. For instance, here’s Tchaikovsky, the composer, writing in the mid-19th century:

It would be vain to try to put into words that immeasurable sense of bliss which comes over me directly a new idea awakens in me and begins to assume a different form. I forget everything and behave like a madman. Everything within me starts pulsing and quivering; hardly have I begun the sketch ere one thought follows another.

Another of my subjects, a neuroscientist and an inventor, told me, “There is no greater joy that I have in my life than having an idea that’s a good idea. At that moment it pops into my head, it is so deeply satisfying and rewarding … My nucleus accumbens is probably going nuts when it happens.” (The nucleus accumbens, at the core of the brain’s reward system, is activated by pleasure, whether it comes from eating good food or receiving money or taking euphoria-inducing drugs.)

As for how these ideas emerge, almost all of my subjects confirmed that when eureka moments occur, they tend to be precipitated by long periods of preparation and incubation, and to strike when the mind is relaxed—during that state we called REST. “A lot of it happens when you are doing one thing and you’re not thinking about what your mind is doing,” one of the artists in my study told me. “I’m either watching television, I’m reading a book, and I make a connection … It may have nothing to do with what I am doing, but somehow or other you see something or hear something or do something, and it pops that connection together.”

Many subjects mentioned lighting on ideas while showering, driving, or exercising. One described a more unusual regimen involving an afternoon nap: “It’s during this nap that I get a lot of my work done. I find that when the ideas come to me, they come as I’m falling asleep, they come as I’m waking up, they come if I’m sitting in the tub. I don’t normally take baths … but sometimes I’ll just go in there and have a think.”

Some of the other most common findings my studies have suggested include:

Many creative people are autodidacts. They like to teach themselves, rather than be spoon-fed information or knowledge in standard educational settings. Famously, three Silicon Valley creative geniuses have been college dropouts: Bill Gates, Steve Jobs, and Mark Zuckerberg. Steve Jobs—for many, the archetype of the creative person—popularized the motto “Think different.” Because their thinking is different, my subjects often express the idea that standard ways of learning and teaching are not always helpful and may even be distracting, and that they prefer to learn on their own. Many of my subjects taught themselves to read before even starting school, and many have read widely throughout their lives. For example, in his article “On Proof and Progress in Mathematics,” Bill Thurston wrote:

My mathematical education was rather independent and idiosyncratic, where for a number of years I learned things on my own, developing personal mental models for how to think about mathematics. This has often been a big advantage for me in thinking about mathematics, because it’s easy to pick up later the standard mental models shared by groups of mathematicians.

This observation has important implications for the education of creatively gifted children. They need to be allowed and even encouraged to “think different.” (Several subjects described to me how they would get in trouble in school for pointing out when their teachers said things that they knew to be wrong, such as when a second-grade teacher explained to one of my subjects that light and sound are both waves and travel at the same speed. The teacher did not appreciate being corrected.)

Many creative people are polymaths, as historic geniuses including Michelangelo and Leonardo da Vinci were. George Lucas was awarded not only the National Medal of Arts in 2012 but also the National Medal of Technology in 2004. Lucas’s interests include anthropology, history, sociology, neuroscience, digital technology, architecture, and interior design. Another polymath, one of the scientists, described his love of literature:

I love words, and I love the rhythms and sounds of words … [As a young child] I very rapidly built up a huge storehouse of … Shakespearean sonnets, soliloquies, poems across the whole spectrum … When I got to college, I was open to many possible careers. I actually took a creative-writing course early. I strongly considered being a novelist or a writer or a poet, because I love words that much … [But for] the academics, it’s not so much about the beauty of the words. So I found that dissatisfying, and I took some biology courses, some quantum courses. I really clicked with biology. It seemed like a complex system that was tractable, beautiful, important. And so I chose biochemistry.

The arts and the sciences are seen as separate tracks, and students are encouraged to specialize in one or the other. If we wish to nurture creative students, this may be a serious error.

Creative people tend to be very persistent, even when confronted with skepticism or rejection. Asked what it takes to be a successful scientist, one replied:

Perseverance … In order to have that freedom to find things out, you have to have perseverance … The grant doesn’t get funded, and the next day you get up, and you put the next foot in front, and you keep putting your foot in front … I still take things personally. I don’t get a grant, and … I’m upset for days. And then I sit down and I write the grant again.

Do creative people simply have more ideas, and therefore differ from average people only in a quantitative way, or are they also qualitatively different? One subject, a neuroscientist and an inventor, addressed this question in an interesting way, conceptualizing the matter in terms of kites and strings:

In the R&D business, we kind of lump people into two categories: inventors and engineers. The inventor is the kite kind of person. They have a zillion ideas and they come up with great first prototypes. But generally an inventor … is not a tidy person. He sees the big picture and … [is] constantly lashing something together that doesn’t really work. And then the engineers are the strings, the craftsmen [who pick out a good idea] and make it really practical. So, one is about a good idea, the other is about … making it practical.

Of course, having too many ideas can be dangerous. One subject, a scientist who happens to be both a kite and a string, described to me “a willingness to take an enormous risk with your whole heart and soul and mind on something where you know the impact—if it worked—would be utterly transformative.” The if here is significant. Part of what comes with seeing connections no one else sees is that not all of these connections actually exist. “Everybody has crazy things they want to try,” that same subject told me. “Part of creativity is picking the little bubbles that come up to your conscious mind, and picking which one to let grow and which one to give access to more of your mind, and then have that translate into action.”

In A Beautiful Mind, her biography of the mathematician John Nash, Sylvia Nasar describes a visit Nash received from a fellow mathematician while institutionalized at McLean Hospital. “How could you, a mathematician, a man devoted to reason and logical truth,” the colleague asked, “believe that extraterrestrials are sending you messages? How could you believe that you are being recruited by aliens from outer space to save the world?” To which Nash replied: “Because the ideas I had about supernatural beings came to me the same way that my mathematical ideas did. So I took them seriously.”

Some people see things others cannot, and they are right, and we call them creative geniuses. Some people see things others cannot, and they are wrong, and we call them mentally ill. And some people, like John Nash, are both.