Poland – Mazovia (Warsaw, Radom and Łódź) August 10-12, 2019

Treblinka Concentration Camp. In an operation called Operation Reinhardt, designed for mass murder, Treblinka was one of 3 death camps for Polish Jews (the others were Sobibor and Belzec) that operated from July 1942 to August 1943. 100 km east of Warsaw (and the Warsaw Ghetto), it was in a remote location for secrecy, on a railway line and close to a significant Jewish population.

It was not a concentration camp, but only an extermination camp, as the Jews were unloaded from the cars and killed immediately. 20-30 cattle cars with 100 people arrived at the railway station at least once per day, which was built to resemble a typical station, with fares and other information displayed on the walls.

At its most active, two trains arrived every day, each carrying approximately 2,000. They were separated into men and women, ordered to strip, hair shaven, washed and disinfected and led along a road called “Road to Heaven”. The disabled, elderly and orphan children were taken to pits, shot in the head and burned. The men and women were herded into gas chambers that appeared to be public baths with ceramic tiles and shower heads, ordered to raise their arms over their heads to allow more people inside, and petrol engines were turned on, producing carbon monoxide. It took 25 minutes for them all to die.

There were initially only three killing chambers, but Treblinka was soon enlarged to 10 in the autumn of 1942. Initially, 2-3,000 could be processed in 3 hours, but the efficiency soon improved to 1½ hours. The bodies were pulled out, gold teeth extracted, and all put into large pits. In the winter of 1943, these were dug out and then burned using railway ties as fuel. The clothes were sorted into piles (initially, when not sorted, they tended to rot) and sent to Germany. The guards were SS and Ukrainian prisoners of war, known for their brutality.

An estimated 900,000 were killed here.

.

In the NM “The Dark Side” series, all that remains is a museum – the camp itself was destroyed after its usefulness had ended. Watch a series of videos, one featuring a riveting dialogue from an older man who, as he said, was a bricklayer and then a barber. It became an archaeological dig, and some of the few artifacts discovered are now on display. Free

WARSAW

Warsaw Pass. This is primarily a museum pass with the option of adding transportation. Also includes Hop-on-Hop-off buses, a Chopin piano recital and 10-25% reductions with various tours.

The included museums are (Nomad Mania sites indicated by *): Museum of Warsaw*, Zacheta – National Gallery of Art* (modern and contemporary art), Polin Museum of the History of Polish Jews*, The Fryderyk Chopin Museum*, Copernicus Science Center*, The Heavens of Copernicus Planetarium*, Wilanow Palace Museum and Park*, National Museum of Warsaw*, Royal Lazienni Museum*, Dollhouse Museum*, Palace of Culture and Science Viewing Terrace*, Uiazdowski Castle Center for Contemporary Art, Polish Vodka Museum, Museum of Life Under Communism, two sports stadiums (PGE Narodowy Stadium and Legia Warsaw Stadium, both with guided tours), Archdiocese Museum & Cathedral Centre, The Heritage Monument Interpretation Centre and Praga Museum of Warsaw.

Cost in PLN: 24 hours – 129, 48 hours – 169, 72 hours – 199. In my 24 hours, the value of the attractions was: full adult fare – 293, reduced fare – 154, so it barely paid for itself.

WARSAW GHETTO

It was the largest of all the Jewish ghettos in German-occupied Europe during World War II. The German authorities established it in November 1940. There were over 400,000 Jews imprisoned there in an area of 3.4 km2 (1.3 sq mi), with an average of 9.2 persons per room, barely subsisting on meagre food rations. From the Warsaw Ghetto, Jews were deported to Nazi concentration camps and mass-killing centers. In the summer of 1942, at least 254,000 Ghetto residents were sent to the Treblinka extermination camp during Großaktion Warschau under the guise of “resettlement in the East” throughout the summer. The Germans demolished the ghetto in May 1943 after the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, which had temporarily halted the deportations. The total death toll among the Jewish inhabitants of the Ghetto is estimated to be at least 300,000 killed by bullet or gas, combined with 92,000 victims of rampant hunger and hunger-related diseases, the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, and the casualties of the final destruction of the Ghetto.

Background. Before World War II, Warsaw was one of the most diverse cities in the Second Polish Republic. The majority of Polish Jews lived in the merchant districts of Muranów, Powązki, and Stara Praga, while most ethnic Germans lived in Śródmieście. Over 90% of Catholics lived further away from the bustling commercial and vital center of the capital. The Jewish community was the most prominent, constituting over 88% of the inhabitants of Muranów, with a total of about 32.7% of the population of left-bank Warsaw and 14.9% of the right-bank Warsaw, or 332,938 people in total, according to the 1931 census. Many Jews left the city during the depression. Antisemitic legislation, boycotts of Jewish businesses, and the post-Piłsudski Polish government plans put pressure on Jews in the town. In 1938, the Jewish population of the Polish capital was estimated to be approximately 270,000 people.

The Siege of Warsaw continued until September 29, 1939. On September 10 alone, the Luftwaffe conducted 17 bombing raids on the city; three days later, 50 German planes attacked the city centre, targeting specifically Wola and Żoliborz. In total, some 30,000 people were killed, and 10 percent of the city was destroyed. Along with the advancing Wehrmacht, the Einsatzgruppe EG IV and the Einsatzkommandos rolled into town. On November 7, 1939, the Reichsführer-SS reorganized them into the Sicherheitsdienst (SD).

Meanwhile, the German fifth column members of Selbstschutz (detained by the defenders of Warsaw) were released immediately. The commander of EG IV, SS-Standartenführer Josef Meisinger (the “Butcher of Warsaw”), was appointed chief of police for the newly formed Distrikt Warschau. After the takeover of Warsaw, the German authorities began the registration of the ethnic Germans who were issued the Kennkarte, separate from the rest of the locals. By June 1940, there were 2,500 Reichsdeutsche and 5,500 Volksdeutsche registered in Warsaw. In the next two years, their number more than doubled, in addition to over 50,000 German military personnel.

Creation. By the end of the September campaign, the number of Jews in and around the capital increased dramatically, with thousands of refugees escaping the Polish-German front in any possible way, often on foot. Within a year, the number of refugees in Warsaw surpassed 90,000. Once the partition of the country between Germany and the invading Soviet Union was complete, on October 12, 1939, the General Government was officially established by Adolf Hitler in the occupied area of central Poland. The Nazis formed the Jewish Council (Judenrat) in Warsaw on October 7. It was composed of 24 prominent individuals, led by Adam Czerniaków, who was personally responsible for carrying out German orders. The persecution of Jews began soon thereafter. On October 26, the imposition of Jewish forced labour was announced, to clear the rubble from bomb damage, among similar tasks. One month later, on November 20, the bank accounts of Polish Jews and any deposits exceeding 2,000 zł were blocked. On November 23, all Jewish establishments were ordered to display a Jewish star on doors and windows. Beginning December 1, all Jews older than ten were required to wear a white armband, and on December 11, they were prohibited from using public transportation. On January 26, 1940, the Jews were banned from holding communal prayers ostensibly due to the risk of “spreading epidemics”. The German authorities were introducing food stamps, and the liquidation of all smaller Jewish communities in the vicinity of Warsaw had intensified. The Jewish population of the capital reached 359,827 before the end of the year.

On the orders of Warsaw District Governor, Ludwig Fischer, the Ghetto wall construction started on April 1, 1940, circling the area of Warsaw inhabited predominantly by Jews. The Warsaw Judenrat supervised the work. The Nazi authorities expelled 113,000 ethnic Poles from the neighbourhood, and ordered the relocation of 138,000 Warsaw Jews from the suburbs into the city centre. On October 16, 1940, the creation of the ghetto covering the area of 307 hectares (3.07 km2) was announced officially by the German Governor-General, Hans Frank. The population of the ghetto initially numbered 450,000. Before the Holocaust began, the number of Jews imprisoned there was between 375,000 and 400,000 (about 30% of the general population of the capital). The area of the ghetto constituted only about 2.4% of the overall metropolitan area.

The Germans closed the Warsaw Ghetto to the outside world on November 15, 1940. The wall around it was typically 3 m (9.8 ft) high and topped with barbed wire. Escapees were shot on sight. German police officers from Battalion 61 used to hold victory parties on the days when a large number of prisoners were shot at the ghetto fence. The borders of the ghetto changed, and its overall area was gradually reduced, as outbreaks of infectious diseases, mass hunger, and regular executions decreased the captive population.

The ghetto was divided into two along Chłodna Street, which was excluded from it, due to its local importance at that time (as one of Warsaw’s east-west thoroughfares). The area south-east of Chłodna was known as the “Small Ghetto”, while the area north of it became known as the “Large Ghetto”. The two zones were connected at an intersection of Chłodna with Żelazna Street, where a special gate was built. In January 1942, the gate was removed and a wooden footbridge was built over it, which became one of the postwar symbols of the Holocaust in occupied Poland.

Ghetto administration. The first commissioner of the Warsaw Ghetto, appointed by Fischer, was SA-Standartenführer Waldemar Schön, who also supervised the initial Jewish relocations in 1940. He was an attritionist best known for orchestrating an “artificial famine” (künstliche Hungersnot) in January 1941. Schön had eliminated virtually all food supplies to the ghetto, causing an uproar among the SS upper echelon. He was relieved of his duties by Frank himself in March 1941 and replaced by Kommissar Heinz Auerswald, a “productionist” who served until November 1942. Like in all Nazi ghettos across occupied Poland, the Germans ascribed the internal administration to a Judenrat Council of the Jews, led by an “Ältester” (the Eldest). In Warsaw, this role was relegated to Adam Czerniaków, who chose a policy of collaboration with the Nazis in the hope of saving lives. Adam Czerniaków confided his harrowing experience in nine diaries. In July 1942, when the Germans ordered him to increase the contingent of people to be deported, he committed suicide.

Czerniaków’s collaboration with the German occupation policies was a paradigm for the attitude of the majority of European Jews vis à vis Nazism. Although his personality as president of the Warsaw Judenrat may not become as infamous as Chaim Rumkowski, Ältester of the Łódź Ghetto, the SS policies he had followed were systematically anti-Jewish.

Czerniakow’s first draft of October 1939 for organizing the Warsaw Judenrat was merely a rehash of conventional kehilla departments: chancellery, welfare, rabbinate, education, cemetery, tax department, accounting, and vital statistics. But the Kehilla was an anomalous institution. Throughout its history in czarist Russia, it also served as an instrument of the state, obligated to carry out the regime’s policies within the Jewish community, even though these policies were frequently oppressive and specifically anti-Jewish.

The Council of Elders was supported internally by the Jewish Ghetto Police (Jüdischer Ordnungsdienst), formed at the end of September 1940 with 3,000 men, instrumental in enforcing law and order as well as carrying out German ad-hoc regulations, especially after 1941, when the number of refugees and expellees in Warsaw reached 150,000 or nearly one third of the entire Jewish population of the capital.

Catholics and Poles in the Ghetto. In January 1940, there were 1540 Catholics and 221 individuals of other Christian faith imprisoned in the Ghetto, including Jewish converts. It is estimated that at the time of closure of the ghetto, there were around 2,000 Christians, and the number possibly rose eventually to over 5,000. Many of these people considered themselves Polish, but due to Nazi racial criteria, they were classified by German authorities as Jewish. Within the ghetto, there were three Christian churches: the All Saints Church, St. Augustine’s Church and the Church of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin Mary. All Saints Church served Jewish Christians who were detained in the ghetto. At that time, the parish priest, Marceli Godlewski, known for his antisemitism before the war, became involved in helping them. At the rectory of the parish, the priest sheltered and helped many escape, including Ludwik Hirszfeld, Louis-Christophe Zaleski-Zamenhof and Wanda Zamenhof-Zaleska. For his actions in 2009, he was posthumously awarded the Righteous Among the Nations medal.

Conditions. During the first year and a half, thousands of Polish Jews, as well as some Romani people from smaller towns and the countryside, were brought into the Ghetto. Nevertheless, the typhus epidemics and starvation kept the inhabitants at about the same number. An average daily food ration in 1941 for Jews in Warsaw was limited to 184 calories, compared to 699 calories allowed for the gentile Poles and 2,613 calories for the Germans. In August, the rations fell to 177 calories per person. The German authorities were solely responsible for the arrival of food aid, which typically consisted of dry bread, flour, and potatoes of the lowest quality, as well as groats, turnips, and a small monthly supplement of margarine, sugar, and meat.

The only real means of survival was the smuggling of food and bartering, with men, women and children all taking part in it. Up to 80 percent of the food consumed in the Ghetto was brought in illegally. Private workshops were created to manufacture goods to be sold secretly on the Aryan side of the city. Foodstuffs were often smuggled by children alone who crossed the Ghetto wall in any way possible by the hundreds, sometimes several times a day, returning with goods that could weigh as much as they did. Smuggling was often the only source of subsistence for the Ghetto inhabitants, who would otherwise have died of starvation. Unemployment leading to a lack of funds was a significant problem in the ghetto.

Education and culture. Despite the grave hardships, life in the Warsaw Ghetto included educational and cultural activities conducted by its underground organizations. Hospitals, public soup kitchens, orphanages, refugee centers, and recreation facilities were established, along with a comprehensive school system. Some schools were illegal and operated under the guise of soup kitchens. There were secret libraries, classes for the children and even a symphony orchestra. Rabbi Alexander Friedman, secretary-general of Agudath Israel of Poland, was one of the Torah leaders in the Warsaw Ghetto; he organized an underground network of religious schools, including “a Yesodei HaTorah school for boys, a Bais Yaakov school for girls, a school for elementary Jewish instruction, and three institutions for advanced Jewish studies”. These schools, operating under the guise of kindergartens, medical centers and soup kitchens, were a place of refuge for thousands of children and teens, and hundreds of teachers. In 1941, when the Germans gave official permission to the local Judenrat to open schools, these schools came out of hiding and began receiving financial support from the official Jewish community. The former cinema Femina was converted into a theatre during this period. The Jewish Symphonic Orchestra performed in several rooms, including Femina.

Manufacture of German military supplies. Not long after the Ghetto was closed off from the outside world, several German war profiteers such as Többens and Schultz appeared in the capital. Initially, they served as intermediaries between the high command and the Jewish-run workshops. By spring 1942, the Stickerei Abteilung Division, with its headquarters at Nowolipie 44 Street, had already employed 3,000 workers producing shoes, leather products, sweaters, and socks for the Wehrmacht. Other divisions were also making fur and wool sweaters, guarded by the Werkschutz police. Some 15,000 Jews were working in the Ghetto for Walter C. Többens from Hamburg, a convicted war criminal, including at his factories on Prosta and Leszno Streets among other locations. His Jewish labour exploitation was a source of envy for other Ghetto inmates living in fear of deportations. In early 1943, Többens secured for himself the appointment of a Jewish deportation commissar in Warsaw, aiming to keep his workforce secure and maximize profits. In May 1943, Többens transferred his businesses, including 10,000 Jewish slave workers, to the Poniatowa concentration camp barracks. Fritz Schultz took his manufacture along with 6,000 Jews to the nearby Trawniki concentration camp.

Treblinka deportations. Approximately 100,000 Ghetto inmates had already died of hunger-related diseases and starvation before the mass deportations started in the summer of 1942. Earlier that year, during the Wannsee Conference near Berlin, the Final Solution was initiated. It was a secretive plan to mass-murder Jewish inhabitants of the General Government. The techniques used to deceive victims were based upon experience gained at the Chełmno extermination camp (Kulmhof). The ghettoized Jews were rounded up, street by street, under the guise of “resettlement” and marched to the Umschlagplatz holding area. From there, they were sent aboard Holocaust trains to the Treblinka death camp, built in a forest 80 kilometres (50 mi) northeast of Warsaw. The operation was headed by SS-Sturmbannführer Hermann Höfle, the German Resettlement Commissioner, on behalf of Sammern-Frankenegg. Upon learning of this plan, Adam Czerniaków, leader of the Judenrat Council, committed suicide. He was replaced by Marc Lichtenbaum, tasked with managing roundups with the aid of Jewish Ghetto Police. No one was informed about the real state of affairs.

The extermination of Jews using poisonous gases was carried out at Treblinka II under the auspices of Operation Reinhard, which also included Bełżec, Majdanek, and Sobibór death camps. About 254,000 Warsaw Ghetto inmates (or at least 300,000 by different accounts) were sent to Treblinka during the Grossaktion Warschau, and murdered there between Tisha B’Av (July 23) and Yom Kippur (September 21) of 1942. The ratio between Jews killed on the spot by Orpo and Sipo during roundups, and those deported was approximately 2 percent.

For eight weeks, the deportations of Jews from Warsaw to Treblinka continued daily via two shuttle trains: each transport carrying about 4,000 to 7,000 people, crying for water; 100 people to a cattle truck. The first daily trains rolled into the camp early in the morning, often after an overnight wait at a layover yard, and the second, in mid-afternoon. Dr. Janusz Korczak, a renowned educator, took his orphanage children to Treblinka in August 1942. He was offered a chance to escape by Polish friends and admirers, but he chose instead to share the fate of his life’s work. All new arrivals were immediately escorted to the undressing area by the Sonderkommando squad that managed the arrival platform and then taken to the gas chambers. The stripped victims were suffocated to death in batches of 200 with the use of carbon monoxide gas. In September 1942, new gas chambers were built, which could kill as many as 3,000 people in just 2 hours. Civilians were prohibited from approaching the camp area. In the last two weeks of Großaktion Warschau, ending on September 21, 1942, some 48,000 Warsaw Jews were deported to their deaths. The previous transport with 2,200 victims from the Polish capital included the Jewish police involved with deportations, and their families. In October 1942, the Jewish Combat Organization (ŻOB) was formed and tasked with opposing further deportations. It was led by 24–year–old Mordechai Anielewicz. Meanwhile, between October 1942 and March 1943, Treblinka received transports of almost 20,000 foreign Jews from the German Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia via Theresienstadt, and from Bulgarian-occupied Thrace, Macedonia, and Pirot following an agreement with the Nazi-allied Bulgarian government.

By the end of 1942, it was clear that the deportations were to their deaths. The underground activity of Ghetto resistors in the group Oyneg Shabbos increased after learning that the transports for “resettlement” led to the mass killings. Also in 1942, Polish resistance officer Jan Karski reported to the Western governments on the situation in the Ghetto and on the extermination camps. Many of the remaining Jews decided to resist further deportations and began to smuggle in weapons, ammunition and supplies.

Ghetto Uprising and the final destruction of the ghetto. On January 18, 1943, after almost four months without deportations, the Germans suddenly entered the Warsaw Ghetto intent upon further roundups. Within hours, some 600 Jews were shot and 5,000 others removed from their residences. The Germans expected no resistance, but the action was brought to a halt by hundreds of insurgents armed with handguns and Molotov cocktails.

Preparations to resist had been going on since the previous autumn. The first instance of Jewish armed struggle in Warsaw had begun. The underground fighters from ŻOB (Żydowska Organizacja Bojowa: Jewish Combat Organization) and ŻZW (Żydowski Związek Wojskowy: Jewish Military Union) initially achieved considerable success, taking control of the Ghetto. They then barricaded themselves in the bunkers and built dozens of fighting posts, stopping the expulsions. Taking further steps, several Jewish collaborators from Żagiew were also executed. An offensive against the Ghetto underground launched by Von Sammern-Frankenegg was unsuccessful. He was relieved of duty by Heinrich Himmler on April 17, 1943 and court-martialed.

The final battle started on the eve of Passover on April 19, 1943, when a Nazi force consisting of several thousand troops entered the ghetto. After initial setbacks, 2,000 Waffen-SS soldiers under the field command of Jürgen Stroop systematically burned and blew up the ghetto buildings, block by block, rounding up or murdering anybody they could capture. Significant resistance ended on April 28, and the Nazi operation officially ended in mid-May, symbolically culminating with the demolition of the Great Synagogue of Warsaw on May 16. According to the official report, at least 56,065 people were killed on the spot or deported to German Nazi concentration and death camps (Treblinka, Poniatowa, Majdanek, Trawniki). The site of the Ghetto became the Warsaw concentration camp.

Historic Centre of Warsaw. A World Heritage Site, it is the youngest Old Town in the world, as Warsaw was almost destroyed in World War II and subsequently rebuilt to resemble its pre-war state.

The oldest part of Warsaw is bounded by the Wybrzeże Gdańskie (Gdańsk Boulevards), along with the bank of the Vistula River, Grodzka, Mostowa, and Podwale Streets. It is one of the most prominent tourist attractions in Warsaw. The heart of the area is the Old Town Market Place, which is rich in restaurants, cafés, and shops. Surrounding streets feature medieval architecture, such as the city walls, St. John’s Cathedral, and the Barbican, which links the Old Town with Warsaw’s New Town.

The Old Town was established in the 13th century. Initially surrounded by an earthwork rampart, it was fortified with brick city walls before 1339. The town originally grew up around the castle of the Dukes of Mazovia, which later became the Royal Castle of Mazovia. The Market Square (Rynek Starego Miasta) was laid out sometime in the late 13th or early 14th century, along the main road linking the castle with the New Town to the north.

Until 1817, the Old Town’s most notable feature was the Town Hall, built before 1429. In 1701, the square was rebuilt by Tylman Gamerski, and in 1817, the Town Hall was demolished. Since the 19th century, the four sides of the Market Square have borne the names of four notable Poles who once lived on the respective sides: Ignacy Zakrzewski (south), Hugo Kołłątaj (west), Jan Dekert (north) and Franciszek Barss (east).

In the early 1910s, Warsaw’s Old Town was home to the prominent Yiddish writer Alter Kacyzne, who later depicted life there in his 1929 novel, Shtarke un Shvache (“The Strong and the Weak”). As described in the novel, the Old Town at that time was a slum neighbourhood, with low-income families—some Jewish, others Christian—living in very crowded subdivided tenements that had once been aristocrats’ palaces. Parts of it were bohemian, with painters and artists having their studios, while some streets were a Red-light district housing brothels.

In 1918, the Royal Castle once again became the seat of Poland’s highest authorities: the President of Poland and his chancellery. In the late 1930s, during Stefan Starzyński’s mayoralty, the municipal authorities began refurbishing the Old Town and restoring it to its former glory. The Barbican and the Old Town Market Place were partly restored. These efforts, however, were brought to an end by the outbreak of World War II.

During the Invasion of Poland (1939), much of the district was severely damaged by the German Luftwaffe, which targeted the city’s residential areas and historic landmarks in a campaign of terror bombing. Following the Siege of Warsaw, parts of the Old Town were rebuilt, but immediately after the Warsaw Uprising (August–October 1944), what had been left standing was systematically blown up by the German Army. A statue commemorating the Uprising, “the Little Insurgent,” now stands on the Old Town’s medieval city wall.

After World War II, the Old Town was meticulously rebuilt. In an effort at anastylosis, as many of the original bricks as possible were reused. However, the reconstruction was not always accurate to prewar Warsaw; sometimes deference was given to an earlier period, an attempt was made to improve on the original, or an authentic-looking facade was created to cover a more modern building. The rubble was sifted for reusable decorative elements, which were reinserted into their original places. Bernardo Bellotto’s 18th-century vedute, as well as the drawings of pre-World War II architecture students, were used as essential sources in the reconstruction effort. However, Bellotto’s drawings had not been entirely immune to artistic license and embellishment, and in some cases, this was transferred to the reconstructed buildings.

Squares. The Old Town Market Place (Rynek Starego Miasta), which dates back to the end of the 13th century, is the true heart of the Old Town, and until the end of the 18th century, it was the heart of all of Warsaw. Here, the representatives of guilds and merchants met in the Town Hall (built before 1429, pulled down in 1817), and fairs and the occasional execution were held. The houses around it represented the Gothic style until the great fire of 1607, after which they were rebuilt in the late Renaissance style.

Castle Square (Plac Zamkowy) is the first view of the reconstructed Old Town for visitors approaching from the more modern center of Warsaw. It is an impressive sight, dominated by Zygmunt’s Column, which towers above the beautiful historic houses of the Old Town. Enclosed between the Old Town and the Royal Castle, Castle Square is steeped in history. Here was the gateway leading into the city, known as the Kraków Gate (Brama Krakowska). It was developed in the 14th century and continued to be a defensive area for the kings. The square was in its glory in the 17th century, when Warsaw became the country’s capital. It was here in 1644 that King Władysław IV erected the column to glorify his father, Sigismund III Vasa, who is best known for moving the capital of Poland from Kraków to Warsaw. The Museum of Warsaw is also located there.

Canon Square, behind St. John’s Cathedral, is a small triangular square. Its name comes from the 17th-century tenement houses which belonged to the canons of the Warsaw chapter. Some of these canons were quite famous, such as Stanisław Staszic, who was the co-author of the Constitution of May 3, 1791. Formerly, it was a parochial cemetery, from which a Baroque figure of Our Lady from the 18th century remains. In the middle of the square is the bronze bell of Warsaw, which Grand Crown Treasurer Jan Mikołaj Daniłowicz founded in 1646 for the Jesuit Church in Jarosław. The bell was cast in 1646 by Daniel Tym, the designer of Zygmunt’s Column. Where the Canon Square meets the Royal Square is a covered passage built for Queen Anna Jagiellon in the late 16th century and extended in the 1620s after Michał Piekarski’s failed attempt to assassinate King Sigismund III Vasa as he was entering the Cathedral in 1620. Also, the thinnest house in Warsaw is located there.

Recognition. In 1980, Warsaw’s Old Town was placed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites as “an outstanding example of a near-total reconstruction of a span of history covering the 13th to the 20th century.

The main square is lovely, with connected four-story buildings, dormer windows on the roof, and often an extension of the building above. Facades feature a range of light pastel colours with floral designs, gilding, and art. The center of the square is full of tables and art for sale. All the streets in the old town are cobblestone.

I purchased the 24-hour Warsaw Pass and took a big walkabout to see all the museums listed on the pass. It was a big walk day.

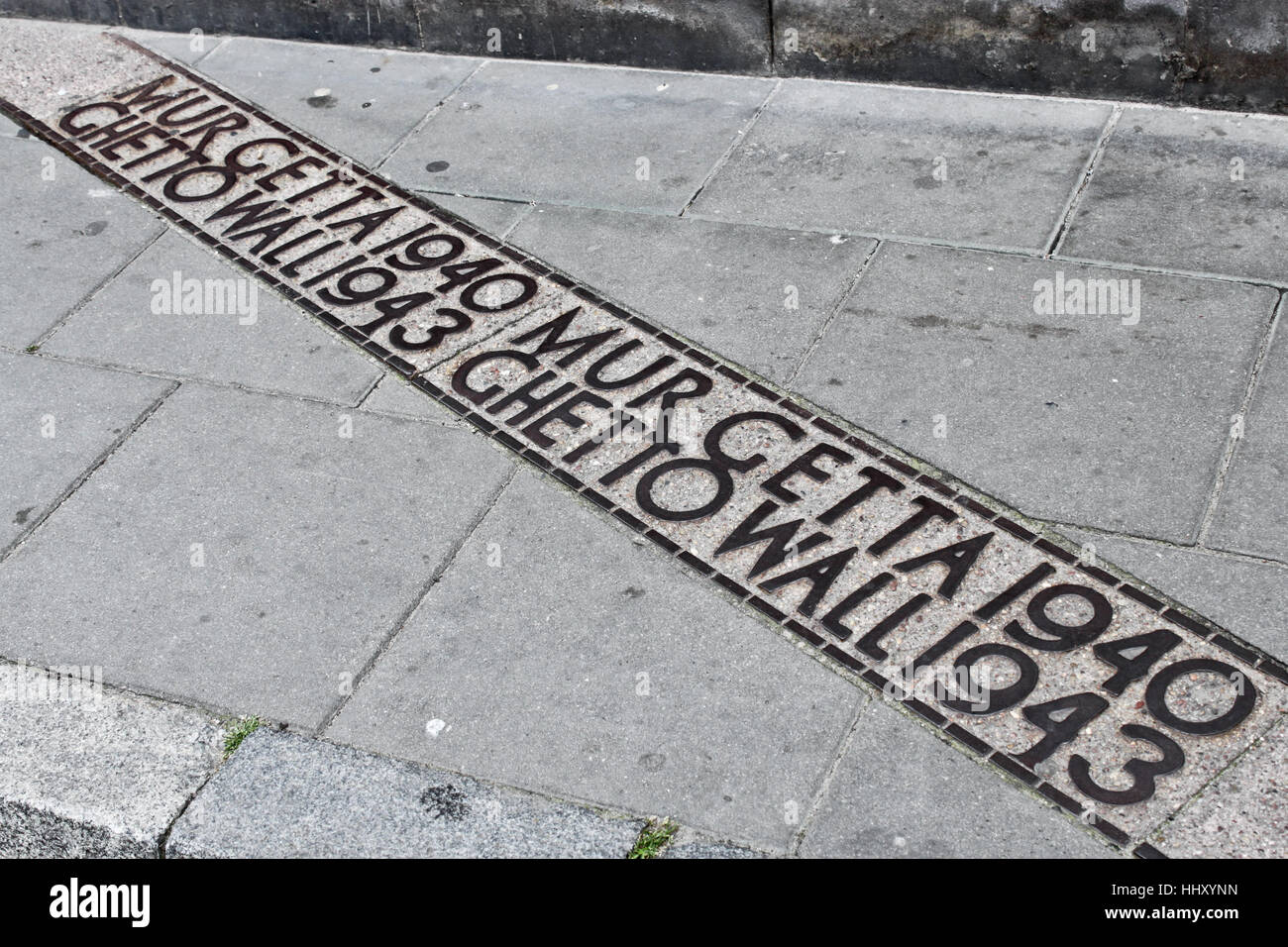

Vestiges of the Jewish Ghetto in Warsaw. The German forces levelled the entire city district according to order from Adolf Hitler after the suppression of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943.

The ghetto was almost entirely levelled during the Uprising; however, several buildings and streets survived, mainly in the “small ghetto” area, which had been included in the Aryan part of the city in August 1942 and was not involved in the fighting. In 2008 and 2010, Warsaw Ghetto boundary markers were built along the borders of the former Jewish quarter, where from 1940–1943 stood the gates to the ghetto, wooden footbridges over Aryan streets, and the buildings important to the ghetto inmates. The four buildings at 7, 9, 12 and 14 Próżna Street are among the best-known original residential buildings that in 1940–41 housed Jewish families in the Warsaw Ghetto. They have largely remained empty since the war. The street is a focus of the annual Warsaw Jewish Festival. Between 2011 and 2013, buildings at numbers 7 and 9 underwent extensive renovations, transforming them into office space.

The Nożyk Synagogue also survived the war. It was used as a horse stable by the German Wehrmacht. The synagogue has been restored today and is once again in use as an active synagogue. The best-preserved fragments of the ghetto wall are located at 55 Sienna Street, 62 Złota Street, and 11 Waliców Street (the last two being the walls of pre-war buildings). There are two Warsaw Ghetto Heroes’ monuments, unveiled in 1946 and 1948, near the place where the German troops entered the ghetto on 19 April 1943. In 1988, a stone monument was built to mark the Umschlagplatz.

There is also a small memorial at the U.L. Mila 18 to commemorate the site of the Socialist ŻOB underground headquarters during the Ghetto Uprising. In December 2012, a controversial statue of a kneeling and praying Adolf Hitler was installed in a courtyard of the Ghetto. The artwork by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, entitled “HIM”, has received mixed reactions worldwide. Many feel that it is unnecessarily offensive, while others, such as Poland’s chief rabbi, Michael Schudrich, think that it is thought-provoking, even “educational”.

Dollhouse Museum. This is a fascinating museum located in the Palace of Culture. With 130 dollhouses, many handmade but most commercial, there are businesses, altars, chapels, hospitals and clinics, schools, individual rooms, and more, all featuring tiny trinkets. They are from all over the world, especially England, Germany and France. PLN 20, reduced 16*

I then wasted an hour walking to Chopin Street, which was kilometres away from the Chopin Museum. However, near it was the Reagan Monument.

Ronald Reagan Monument. This bronze upper torso is set on a red granite lectern featuring the Seal of the President of the United States. The sign had a letter from Nancy Reagan

.

National Museum. From medieval art to modern, I appreciated Jacek Malczewski (1854-1929) the most, a great artist who worked in Polish design, glass, porcelain, and clocks, as well as creating amazing kontush sashes. PLN 20, 10* reduced

Polish Army Museum. Outside planes and tanks, inside, besides all the weapons and armour, uniforms, and medals, is some excellent art, the highlight. 15, 8 reduced

Fryderyk Chopin (1810 – 1849) was a Polish composer, pianist and music teacher. He was a music genius recognized from an early age and began composing music soon after starting music lessons at the age of 6. The essence of his music was improvisation, characterized by revolutionary ideas and a unique style. His main home was in Paris from age 21, but he moved around Europe and never returned to Poland. The museum features sheet music, letters, engravings, a few personal momentos, and multiple interactive multimodal stations, all of which are very boring. However, the former Grinski Palace was lovely. PLN 22, 17 reduced*

Heavens of Copernicus. This is the planetarium associated with the Copernicus Science Center. In the dome, a variety of movies are shown, including 2D and 3D films, children’s films, live shows, and meetings with scientists. When I arrived, the next show was 2 hours later – Dawn of the Space Age, about early space flights, which did not interest me much. Exhibits on the 3rd and 1st floors: geostationary orbit (35,786 km above the equator), moving at 3.07 km/s to maintain its path, asteroids, the ISS, satellites, and climate. PLN 33, 22 reduced*

Copernicus Science Centre. This is filled with great interactive science exhibits, including a large one on water. These science museums can be entertaining for all, especially children. PLN 33, 22 reduced*.

Museum of Warsaw. A series of small rooms coming off a central stair, each profiling some aspect of Warsaw: clocks, relics, Warsaw packaging, silverware, portraits, medals, bronzes, clothing, photographs, architectural drawings, Warsaw monuments, postcards, history of tenement houses, archaeology, etc. 20, 15 reduced*

Polin Museum of Polish Jews’ History. Spanning the last 1000 years of Jewish history in Poland, this excellent museum offers a comprehensive overview of Jewish history from biblical times to the present. Follow a fixed

Zacheta – National Gallery of Art. This contemporary art museum has the usual “non-art”. PLN 20, 15 reduced. Circuit with as much information as you want. PLN 40, 27 reduced.

Lazienki Palace (Palace on the Water). PLN 40, 27 reduced*

Fryderyk Chopin Piano Recital. A ticket is necessary, and the clerk at the Warsaw Pass office made a reservation for the 6 pm concert with pianist Piotr Latoszynski. I do not know classical music and only recognized the last piece, but it was terrific piano playing. Chopin had very dynamic music. First were the 24 Preludes, Opus 28, then 4 Etudes, Opus 10 (3,4,5 and 12), Valse, Opus 64 (2), all very enjoyable, and then the last Polonaise in A flat minor, Opus 53, that anyone would recognize. A bonus was the mead liquor at halftime, where I met a couple from the Bahamas.

Day 2

On day 2 in Warsaw, I saw all the places not included on the Warsaw Pass and other free sights.

Targowisko Banacha. This former market is now closed, surrounded by a metal fence and in a state of dereliction.

Warsaw Spire. This is a complex of Neomodern office buildings, comprising a 220m central tower with a hyperboloid glass façade, Warsaw Spire A, and two 55-metre auxiliary buildings, Warsaw Spire B and C. The central tower is the second-tallest building in Warsaw and the tallest in Poland.

The European Border and Coast Guard Agency (FRONTEX) has been headquartered on the 6th to 13th floors of the building since 2012.

In December 2014, a large neon sign with the words “Kocham Warszawę” (“I love Warsaw”) was installed on the upper floors of the partially constructed central tower. The building was topped out in April 2015. The neon sign was removed in 2015, and a more advanced version returned permanently.

This business tower is a semicircle shape with a 12-story building next door. It has a dramatic stainless canopy over the entry.

Rondo 1. This is a new 37-story business tower featuring a glass/round corner exterior, as well as extensive stainless steel in the lobby.

Warsaw Financial Center. Built in 1997-98, this skyscraper is 165m tall, topped with a 20m antenna mast. The building was constructed to comply with all applicable building codes of the United States, including provisions for an emergency generator and its associated water tanks. Amenities include a 6-floor parking lot, a Bank Pekao branch, and a Starbucks, as well as 16 elevators.

This is a 31-story business tower, slightly older. It can’t be entered past the lobby.

Palace of Culture and Science. Constructed between 1952 and 1955 as a gift from the Soviet Union to the people of Poland, it is 237m high, the tallest building in Poland and the 6th-tallest building in the European Union. It houses various public and cultural institutions such as an 8-screen cinema, four theaters, two museums (Museum of Evolution and Museum of Technology), , offices, bookshops, a large swimming pool, an auditorium hall for 3,000 people called Congress Hall, an accredited university, Collegium Civitas, on the 11th and 12th floors, libraries, sports clubs, and authorities of the Polish Academy of Sciences. The architecture is closely related to several similar skyscrapers built in the Soviet Union during the same era, with influences from Polish and American Art Deco styles. The Palace was also the tallest clock tower in the world until the installation of a clock mechanism on the NTT Docomo Yoyogi Building in Tokyo, Japan.

The building was initially known as the Palace of Culture and Science, but Stalin’s name was removed from the colonnade, interior lobby, and one of the building’s sculptures. Its nicknames are Pekin (“Beijing”, due to its abbreviated name PKiN) and Pajac (“clown”, a word that sounds similar to Pałac). Other less common names include Stalin’s syringe, the Elephant in Lacy Underwear, Russian Wedding Cake, or even Chuj Stalina (Stalin’s Dick).

The Rolling Stones played here in 1967, marking the first time a major Western rock group had performed behind the Iron Curtain. In 1985, it hosted the historic Leonard Cohen concert,

Terrace. On the 30th floor is a well-known tourist attraction with a panoramic view of the city. PLN 20, 10 reduced

Various colours light it at night.

Controversy. Viewed as a reminder of Soviet influence over the Polish People’s Republic, mainly due to its construction during mass violations of human rights under Joseph Stalin. Many groups have called for its demolition.

A much older stone building in the Modern Architecture series. Past the terrace is a several-story clock tower with a spire. Lower square towers are on each corner. The ceiling lines are festooned with short columns.

This is where I purchased my Warsaw Pass, but the line for tickets to the Terrace was extremely long. I came back at 7:30.

Złota 44. This residential skyscraper, built from 2009 to 2013, is 192m high (the 6th tallest in Warsaw) with 52 stories. The name Złota 44 originates from the building’s address, located on Złota (“Golden”) Street, adjacent to the Palace of Culture and Science and the Złote Tarasy shopping center.

The 287 apartments with nine interior design variants on the 9th to the 52nd floors have a home management system, access to a 10,000 bottle wine cellar with a tasting room, a 25-meter swimming pool, a jacuzzi, massage rooms, Finnish sauna, a steam room, an outdoor terrace, private cinema with a golf simulator, a playroom for children and conference rooms. The price per square meter ranges from 24,000 PLN to 40,000 PLN.

It was sold in 2014 for €50 million, a small fraction of its construction cost. It features a dramatic inward-curving north section. The concierge was very unfriendly – I asked to sit to write this and he said no.

Zlote Tarasy. A commercial, office, and entertainment complex located next to the Warszawa Centralna railway station, it opened in 2007. It includes 200 shops and restaurants (the first Hard Rock Cafe and the first Burger King in the company’s second attempt to compete with McDonald’s in Poland), a hotel, a multiplex cinema (8 screens, 2560 seats) and an underground parking garage for 1,400 cars. A transparent roof covers its signature central indoor courtyard, designed for concerts and similar events. The building cost $500 million.

Across the street from Zlota 44 is a completely round, 4-story shopping mall, all covered with a dramatic, multi-shape geodesic glass roof. Glass walkways connect the floors. A 4-story, round, glass-roofed tower is located on the northeast corner, housing the escalators.

Warsaw Central Railway Station. A very modern station, it has tracks below and a 2-story mall on the main building.

Wilanów Palace Museum and Park is a royal palace. It survived Poland’s partitions and both World Wars, serving as a reminder of the culture of the Polish state as it was before the misfortunes of the 18th century.

It is one of Poland’s most important monuments. The Palace’s museum, established in 1805, is a repository of the country’s royal and artistic heritage.

It was built for King John III Sobieski in the last quarter of the 17th century and was later enlarged by other owners. It represents the characteristic type of baroque suburban residence built entre cour et jardin (between the entrance court and the garden). Its architecture is original, a merger of generally European art with distinctively Polish building traditions. It glorifies the Sobieski family, especially the military triumphs of the king.

After the death of John III Sobieski in 1696, the palace was owned by his sons and later by the famous magnate families of Sieniawskis, Czartoryskis, Lubomirskis, Potockis, and the Branicki family. In 1720, the property was purchased by Polish stateswoman Elżbieta Sieniawska, who enlarged the palace. Between 1730 and 1733, it was the residence of Augustus II the Strong, also a king of Poland, and after his death, it became the property of Sieniawska’s daughter, Maria Zofia Czartoryska. Every owner changed the interiors of the palace, as well as the gardens and grounds, according to the current fashion and needs. In 1778, the estate was inherited by Izabela Lubomirska, also known as The Blue Marquise. She refurbished some of the interiors in the neoclassical style between 1792 and 1793 and built a corps de garde, a kitchen building and a bathroom building. In 1805, Stanisław Kostka Potocki, the owner, opened a museum in a part of the palace, one of the first public museums in Poland. German forces in World War II damaged the palace, but it was not demolished after the 1944 Warsaw Uprising. After the war, the palace was renovated, and most of the collection stolen by Germany was repatriated. In 1962, it was reopened to the public.

Baroque palace, yellow with white trim, statues covering roof lines. Start with the China Rooms – featuring lots of porcelain, art, weaving, gilt candle stands, clocks, wood panelling, and painted ceilings, as well as old and lacquered furniture. Hunting Room. Princess apartments – dresses, furniture, gilt, inlaid floors. Galleries and halls. King’s apartments – 300-year-old velour wallpaper, gilt, painted ceilings, marble, old furniture, art – all over the top. A painting gallery featuring a collection of mediocre art, as well as wonderful painted medallions on the ceilings and carved stucco.

Gardens with grape arbours, hedges, flowers, and sculpted shrubs.

This is approximately 15 kilometres southeast of Warsaw. I came out here with about 20minutes left on my Warsaw Pass.

Poster Museum, Wilanów. There was a lot of great art, but all the posters were in Polish, making it difficult to appreciate them.

Museum of Polish Military Technology. Parked around an old brick fort with many vaults and a fence (that can’t be entered) are a pile of old tanks, armoured vehicles, and artillery. It looks like a parking lot for old junk and isn’t very interesting. All signs are in Polish. Free

Hala Banacha. With a stone façade, the interior features lovely steel girder construction. In a U-shape, it is almost entirely restaurants and bars: one bookstore and one meat market. Downstairs is a supermarket and other businesses.

Prudential Building (Hotel Warszawa). Fronted by a modernist cream stone 12-story tower with a 2-story penthouse, the interior is dramatic – the lobby is glass-roofed, featuring large slabs of black and white marble on the floors and walls, interspersed with wood.

.

National Museum of Ethnography. A traditional Korean house. Fly Away – about birds and their artistic expression with native art. African mythology _ fertility, health and medicine, initiation, household and marital happiness, hunting, sorcery, farming rituals, war, death, social space, sports and games. Free

Nicolaus Copernicus Monument. Positioned on a 5-step red granite block, the great bronze statue is sitting holding a metal cage globe.

Czapski Palace. Also known as the Krasiński, Sieniawski, or Raczyński Palace, it is a good example of rococo architecture in Warsaw. It was constructed around 1686 and has undergone numerous reconstructions. Its present Rococo character dates from 1752–65, when the palace belonged to the Czapski family. The Czapski Palace changed hands at least ten times, including among the Radziwiłłs, Radziejowskis, Zamoyskis, and Czartoryskis. Between 1827 and 1830, Fryderyk Chopin resided here with his family in the building’s south annex.

The palace burned in 1939 after being shelled by German artillery, and priceless paintings and books were destroyed. It was reconstructed in 1948-59 and incorporated into the Warsaw Academy of Fine Arts, with a museum in the Palace’s attic opened in 1985, which holds

This orange/white trim Rococo palace was being completely renovated and gutted inside.

Krasinski Palace. This baroque palace was built from 1688 to 99 by Jan Krasinski, the Governor of Plock. In 1765, it was sold to the crown and has since been known as the Palace of the Commonwealth. It was subsequently renovated, and the gardens were added. After 1795, it was the seat of the judiciary, and after 1918, it became the Supreme Court. In 1944, during the Warsaw Uprising, it was destroyed, renovated and became the National Library. Presently, it houses special collections, early books, prints and drawings and is also the Polish Jazz Archive.

The building is not open to the public, but the gardens and park are accessible to the public.

Monument to the Fallen and Murdered in the East. It was built to commemorate Poles repressed and killed by the Soviets – the Soviet invasion of 1939-41, 1944 and subsequently, especially the 1940 Katyn massacre and the Polish people deported to Siberian labour camps.

It is approximately 7 metres (23 ft) tall and is made out of bronze. The statue shows a pile of religious symbols (Catholic and Orthodox crosses as well as Jewish and Muslim symbols) on a railway flatcar, which is set on tracks. Forty-four railway sleepers extending in front of the flatcar display the names of places from which Polish citizens were deported for use as slave labour in the USSR, and the names of the camps, collective farms, exile villages and various outposts of the gulag that were their destinations, including the mass murder sites used by the Soviet NKVD.

One of the crosses commemorates the priest Stefan Niedzielak, a Katyn activist who was murdered in mysterious circumstances in 1989. The monument also features the Polish Cross of Valour and a Polish eagle, encircled by a rope, with the date of the Soviet invasion of Poland displayed underneath. The monument bears two inscriptions: Poległym pomordowanym na Wschodzie (“For those fallen in the East”), and ofiarom agresji sowieckiej 17.IX.1939. Naród 17.IX.1995 (“For the victims of Soviet aggression 17.IX.1939. The Polish nation 17.IX.1995”).

Sitting in the middle of a boulevard, this very long monument consists of 44 rough bronze railway ties, the first with several hands stretched up, and the rest with names inscribed on them. They lead to a railway car with about 44 crosses, all different sizes and inclines.

Arkadia. This modern 2-story shopping mall features skylights, elevated walkways as crossings, and moving walks as escalators.

Kazimierz Palace (Copper Roof Palace)

Royal Castle

Sigismund’s Column. Located in Castle Square, it is one of Warsaw’s most famous landmarks as well as the first secular monument in the form of a column in modern history. The column and statue commemorate King Sigismund III Vasa, who in 1596 had moved Poland’s capital from Kraków to Warsaw. They were erected in 1643-44 by Sigismund’s son and successor, King Władysław IV Vasa.

On an 8.5m-high Corinthian column (which was initially made of red marble) is a 2.75m-high sculpture of the King in archaistic armour, carrying a cross in one hand and wielding a sword in the other. The column is a total of 22m high and is adorned by four eagles.

The marble column itself was renovated in 1743, 1810, 1821, and 1828, and in 1854, it was surrounded by a fountain featuring marble tritons. Between 1885 and 87, it was replaced with a new column of granite. The fountain and fence were removed between 1927 and 30. On 1 September 1944, during the Warsaw Uprising, the Germans demolished the column, and its bronze statue was severely damaged. After the war, the statue was repaired, and in 1949, it was set up on a new granite column from the Strzegom mine. The original broken pieces of the column can still be seen lying next to the Royal Castle.

Katyn Museum. The Katyn Massacre was a series of mass executions of Polish military officers and intelligentsia carried out by the Soviet Union, specifically the NKVD (“People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs”, aka the Soviet secret police) in April and May 1940. Though the killings occurred in several locations, the massacre is named after the Katyn Forest, where some of the mass graves were first discovered.

The massacre was prompted by NKVD chief Lavrentiy Beria’s proposal to execute all captive members of the Polish officer corps, dated 5 March 1940, approved by the Politburo of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, including its leader, Joseph Stalin. The number of victims is estimated at 22,000. The victims were executed in the Katyn Forest in Russia, the Kalinin and Kharkiv prisons, and elsewhere. Of the total killed, about 8,000 were officers imprisoned during the 1939 Soviet invasion of Poland, another 6,000 were police officers, and the rest were Polish intelligentsia, the Soviets deemed to be “intelligence agents, gendarmes, landowners, saboteurs, factory owners, lawyers, officials, and priests”. As the Polish Army officer class was representative of the multi-ethnic Polish state, the killed also included Ukrainians, Belarusians, and Polish Jews, including the Chief Rabbi of the Polish Army, Baruch Steinberg.

The government of Nazi Germany announced the discovery of mass graves in the Katyn Forest in April 1943. When the London-based Polish government-in-exile asked for an investigation by the International Committee of the Red Cross, Stalin immediately severed diplomatic relations with it. The USSR claimed the Nazis had killed the victims in 1941, and it continued to deny responsibility for the massacres until 1990, when it officially acknowledged and condemned the perpetration of the killings by the NKVD, as well as the subsequent cover-up by the Soviet government.

An investigation conducted by the office of the Prosecutor General of the Soviet Union (1990–1991) and the Russian Federation (1991–2004) confirmed Soviet responsibility for the massacres. Still, they refused to classify this action as a war crime or as an act of mass murder. The investigation was closed because the perpetrators were dead. Since the Russian government would not classify the dead as victims of the Great Purge, formal posthumous rehabilitation was deemed inapplicable.

In November 2010, the Russian State Duma approved a declaration blaming Stalin and other Soviet officials for ordering the massacre.

Background. On 1 September 1939, the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany began. Consequently, Britain and France, obligated by the Anglo-Polish military alliance and the Franco-Polish alliance to attack Germany in the event of such an invasion, demanded that Germany withdraw from Poland. On 3 September 1939, after Germany failed to comply, Britain, France, and most countries of the British Empire declared war on Germany, but provided little military support to Poland. They took minimal military action during what became known as the Phony War.

The Soviet invasion of Poland began on 17 September, under the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact. The Red Army advanced quickly and met little resistance, as Polish forces facing them were under orders not to engage the Soviets. About 250,000 to 454,700 Polish soldiers and police officers were captured and interned by the Soviet authorities. Some were freed or escaped quickly, but 125,000 were imprisoned in camps run by the NKVD. Of these, 42,400 soldiers, mostly of Ukrainian and Belarusian ethnicity serving in the Polish army, who lived in the territories of Poland annexed by the Soviet Union, were released in October. The 43,000 soldiers born in western Poland, then under German control, were transferred to the Germans; in turn, the Soviets received 13,575 Polish prisoners from the Germans.

Soviet repressions of Polish citizens occurred as well over this period. Since Poland’s conscription system required every nonexempt university graduate to become a military reserve officer, the NKVD was able to round up a significant portion of the Polish educated class. According to estimates by the Institute of National Remembrance (IPN), roughly 320,000 Polish citizens were deported to the Soviet Union (this figure is questioned by some other historians, who hold to older estimates of about 700,000-1,000,000). IPN estimates the number of Polish citizens who died under Soviet rule during World War II at 150,000 (a revision of older estimates of up to 500,000). Of the group of 12,000 Poles sent to Dalstroy camp (near Kolyma) in 1940–1941, mostly POWs, only 583 men survived; they were released in 1942 to join the Polish Armed Forces in the East. According to Tadeusz Piotrowski, “during the war and after 1944, 570,387 Polish citizens had been subjected to some form of Soviet political repression”.

As early as 19 September, the head of the NKVD, Lavrentiy Beria, ordered the secret police to create the Main Administration for Affairs of Prisoners of War and Internees to manage Polish prisoners. The NKVD took custody of Polish prisoners from the Red Army. It proceeded to organize a network of reception centres and transit camps and to arrange rail transport to prisoner-of-war camps in the western USSR. The largest camps were located at Kozelsk (near Optina Monastery), Ostashkov (on Stolobny Island in Lake Seliger, near Ostashkov), and Starobelsk. Other camps were at Jukhnovo (rail station Babynino), Yuzhe (Talitsy), rail station Tyotkino (90 kilometres (56 mi) from Putyvl), Kozelshchyna, Oranki, Vologda (rail station Zaonikeevo), and Gryazovets.

Kozelsk and Starobelsk were primarily used for military officers, while Ostashkov was mainly utilized for Polish Scouting, gendarmes, police officers, and prison officers. Some prisoners were members of other groups within the Polish intelligentsia, such as priests, landowners, and legal personnel. The approximate distribution of men throughout the camps was as follows: Kozelsk, 5,000; Ostashkov, 6,570; and Starobelsk, 4,000. They totalled 15,570 men.

According to a report from 19 November 1939, the NKVD had about 40,000 Polish POWs: 8,000-8,500 officers and warrant officers, 6,000-6,500 officers of police, and 25,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers who were still being held as POWs. In December, a wave of arrests resulted in the imprisonment of additional Polish officers. Ivan Serov reported to Lavrentiy Beria on 3 December that “in all, 1,057 former officers of the Polish Army had been arrested”. The 25,000 soldiers and non-commissioned officers were assigned to forced labour (road construction, heavy metallurgy).

Once at the camps, from October 1939 to February 1940, the Poles were subjected to lengthy interrogations and constant political agitation by NKVD officers, such as Vasily Zarubin. The prisoners assumed they would be released soon, but the interviews were in effect a selection process to determine who would live and who would die. According to NKVD reports, if a prisoner could not be induced to adopt a pro-Soviet attitude, he was declared a “hardened and uncompromising enemy of Soviet authority”.

On 5 March 1940, under a note to Joseph Stalin from Beria, six members of the Soviet Politburo — Stalin, Vyacheslav Molotov, Lazar Kaganovich, Kliment Voroshilov, Anastas Mikoyan, and Mikhail Kalinin — signed an order to execute 25,700 Polish “nationalists and counterrevolutionaries” kept at camps and prisons in occupied western Ukraine and Belarus. The reason for the massacre, according to the historian Gerhard Weinberg, was that Stalin wanted to deprive a potential future Polish military of a significant portion of its talent:

It has been suggested that the motive for this terrible step [the Katyn massacre] was to reassure the Germans as to the reality of Soviet anti-Polish policy. This explanation is completely unconvincing given the care with which the Soviet regime kept the massacre secret from the very German government it was supposed to impress. […] A more likely explanation is that [the massacre] should be seen as looking forward to a future in which there might again be a Poland on the Soviet Union’s western border. Since he intended to keep the eastern portion of the country in any case, Stalin could be sure that any revived Poland would be unfriendly. Under those circumstances, depriving it of a large proportion of its military and technical elite would make it weaker.

The Soviet leadership, and Stalin in particular, viewed the Polish prisoners as a “problem” as they might resist being under Soviet rule. Therefore, they decided the prisoners inside the “special camps” were to be shot as “avowed enemies of Soviet authority”.

Executions. The number of victims is estimated at 22,000 after 3 April 1940 – 14,552 prisoners of war (most or all of them from the three camps) and 7,305 prisoners from Byelorussian and Ukrainian SSR’s prisons.

Those who died at Katyn included soldiers (an admiral, two generals, 24 colonels, 79 lieutenant colonels, 258 majors, 654 captains, 17 naval captains, 85 privates, 3,420 non-commissioned officers, and seven chaplains), 200 pilots, government representatives and royalty (a prince, 43 officials), and civilians (three landowners, 131 refugees, 20 university professors, 300 physicians; several hundred lawyers, engineers, and teachers; and more than 100 writers and journalists). In all, the NKVD executed almost half the Polish officer corps.

Not all of the executed were ethnic Poles, because the Second Polish Republic was a multiethnic state, and its officer corps included Belarusians, Ukrainians, and Jews. It is estimated that about 8% of the Katyn massacre victims were Polish Jews. Three hundred ninety-five prisoners were spared from the slaughter, among them Stanisław Swianiewicz and Józef Czapski. They were taken to the Yukhnov camp or Pavlishtchev Bor and then to Gryazovets.

Up to 99% of the remaining prisoners were killed. People from the Kozelsk camp were executed in Katyn Forest; people from the Starobelsk camp were killed in the inner NKVD prison of Kharkiv, and the bodies were buried near the village of Piatykhatky; and police officers from the Ostashkov camp were killed in the internal NKVD prison of Kalinin (Tver) and buried in Mednoye.

The shooting started in the evening and ended at dawn. The first transport, on 4 April 1940, carried 390 people, and the executioners had difficulty killing so many people in one night. The following transports held no more than 250 people. The executions were usually performed with German-made .25 ACP Walther Model 2 pistols supplied by Moscow, but Soviet-made 7.62×38mmR Nagant M1895 revolvers were also used. The executioners used German weapons rather than the standard Soviet revolvers, as the latter were said to offer too much recoil, which made shooting painful after the first dozen executions. Vasily Mikhailovich Blokhin, chief executioner for the NKVD—and quite possibly the most prolific executioner in history—is reported to have personally shot and killed 7,000 of the condemned, some as young as 18, from the Ostashkov camp at Kalinin prison, over 28 days in April 1940.

The killings were methodical. After the condemned individual’s personal information was checked and approved, he was handcuffed and led to a cell insulated with stacks of sandbags along the walls and a heavy, felt-lined door. The victim was told to kneel in the middle of the cell and was then approached from behind by the executioner and immediately shot in the back of the head or neck. The body was carried out through the opposite door and laid in one of the five or six waiting trucks, whereupon the next condemned was taken inside and subjected to the same fate. In addition to muffling by the rough insulation in the execution cell, the pistol gunshots were also masked by the operation of loud machines (perhaps fans) throughout the night. This procedure took place every night, except on the public May Day holiday.

Some 3,000 to 4,000 Polish inmates of Ukrainian prisons and those from Belarus prisons were probably buried in Bykivnia and in Kurapaty, respectively, about 50 women among them. Lieutenant Janina Lewandowska, daughter of Gen. Józef Dowbor-Muśnicki, was the only woman P.O.W. executed during the massacre at Katyn.

Museum of Pawiak Prison. Pawiak Prison took its name from that of the street on which it stood, ulica Pawia (Polish for “Peacock Street”). Pawiak Prison was built between 1829 and 1835. During the 19th century, Warsaw was under Czarist control as it was part of the Russian Empire. During that time, it was the main prison of central Poland, where political prisoners and criminals alike were incarcerated.

During the January 1863 Uprising, the prison served as a transfer camp for Poles sentenced by Imperial Russia to deportation to Siberia. After Poland regained independence in 1918, the Pawiak Prison became Warsaw’s central prison for male criminals. (Females were detained at the nearby Serbia Prison.)

Following the 1939 German invasion of Poland, the Pawiak Prison became a German Gestapo prison, then part of the Nazi concentration-camp system. Approximately 100,000 men and 200,000 women passed through the prison, mostly Home Army members, political prisoners, and civilians taken hostage in street round-ups. An estimated 37,000 inmates were executed, and 60,000 sent to German death and concentration camps. Exact numbers are unknown, as the prison archives were never found.

During the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, the Pawiak Prison became a German assault base. Pawiak jailers, commanded by Franz Bürkl, volunteered to hunt the Jews.

On 19 July 1944, a Ukrainian Wachmeister (guard), Petrenko, and some prisoners attempted a mass jailbreak, supported by an attack from outside, but failed. Petrenko and several others committed suicide. The resistance attack detachment was ambushed and practically annihilated. The next day, in reprisal, the Germans executed over 380 prisoners. As Julien Hirshaut convincingly argues in Jewish Martyrs of Pawiak, it is inconceivable that the prison-escape attempt was a Gestapo-initiated provocation. The Polish underground had approved the plan but backed out without being able to alert those in the prison that the plan was cancelled.

The final transport of prisoners took place on 30 July 1944, two days before the 1 August outbreak of the Warsaw Uprising. Two thousand men and the remaining 400 women were sent to Gross-Rosen and Ravensbrück. Subsequently, the Polish insurgents captured the area but lost it to German forces. On 21 August 1944, the Germans shot an unknown number of remaining prisoners and burned and blew up the buildings.

After World War II, the buildings were not rebuilt. Half of the gateway and three detention cells survive. Since 1990, a surviving basement has housed a museum which, with the Mausoleum of Struggle and Martyrdom, forms the Museum of Independence.

Warsaw Rising Museum.

Keret House. In the NM “Bizzarium” series, it is the narrowest house in the world, measuring 92cms (3.02 ft) at its thinnest and 152cms (4.99 ft) at its widest. The iron structure features two floors, each with a bedroom, a kitchen, a bathroom, and a living area. It features two non-opening windows, with sunlight also entering through translucent glass panels that comprise the walls. The entire interior is painted white, and the building’s electricity is obtained from a neighbouring building. The house has custom water and sewage technology and is not connected to the city-provided water systems. Due to its small size, the building only accommodates a small 2-beverage refrigerator, and occupants must use a ladder to travel from one level to another. Entry is via retractable stairs that, when closed, become the living area. It is classified as an art installation because it does not comply with Polish building codes, despite being used as a residence.

Keret House is situated between 22 Chłodna Street and 74 Żelazna, adjacent to a pre-war house and an apartment building. Keret said that staying at the Keret House is like a “memorial to my family”; his parents’ families died in World War II when Nazi Germany occupied Poland. From the outside, it consists of eight metal panels, with the top and bottom solid and the middle six made of mesh.

It was named after Israeli writer and filmmaker Etgar Keret, who was the building’s first tenant. Keret plans to give the house to a colleague after he moves out.

Prywatne Muzeum Motoryzacji I Techniki, Otrebusy. Primarily a classic car museum featuring some great cars that have been wonderfully restored, the collection also includes armoured personnel carriers, a double-decker bus, and many bicycles. PLN 15.

Sobanski Palace, Guzow. This was once a spectacular palace with a grey lead roof and many roof chimneys, dormers and side towers. However, it is abandoned and completely derelict, although scaffolding covers the front, and some of the center appears to be undergoing renovation.

Nieborow Palace, Nieborow. This is a lovely 3-story yellow manor house in Baroque style. The gardens behind the home are open to the public and feature mature trees, lovely hedges, and flower beds.

LÓDŹ

LODZ GHETTO. The Łódź Ghetto or Litzmannstadt Ghetto (after the Nazi German name of Łódź) was a World War II ghetto established by the Nazi German authorities for Polish Jews and Roma following the 1939 invasion of Poland. It was the second-largest ghetto in all of German-occupied Europe after the Warsaw Ghetto.

On 30 April 1940, when the gates closed on the ghetto, it housed 163,777 residents. Because of its remarkable productivity, the ghetto managed to survive until August 1944. In the first two years, it absorbed almost 20,000 Jews from liquidated ghettos in nearby Polish towns and villages, as well as 20,000 more from the rest of German-occupied Europe. After the wave of deportations to Chełmno death camp beginning in early 1942, and despite a stark reversal of fortune, the Germans persisted in eradicating the ghetto: they transported the remaining population to Auschwitz and Chełmno extermination camps, where most were murdered upon arrival. It was the last ghetto in occupied Poland to be liquidated. A total of 210,000 Jews passed through it, but only 877 remained hidden when the Soviets arrived. About 10,000 Jewish residents of Łódź, who used to live there before the invasion of Poland, survived the Holocaust elsewhere.

Establishment. When German forces occupied Łódź on 8 September 1939, the city had a population of 672,000 people. Over 230,000 of them were Jewish, accounting for 31.1% of the total, according to statistics.

By 1 October 1940, the relocation of the ghetto inmates was to have been completed, and the city’s downtown core declared Judenrein (cleansed of its Jewish presence). The new German owners pressed for the ghetto size to be shrunk beyond all sense to have their factories registered outside of it. Łódź was a multicultural mosaic before the war began, with about 8.8% ethnic German residents on top of Austrian, Czech, French, Russian and Swiss business families adding to its bustling economy.

The securing of the ghetto system was preceded by a series of anti-Jewish measures as well as anti-Polish measures meant to inflict terror. The Jews were forced to wear the yellow badge. The Gestapo expropriated their businesses. After the invasion of Poland, many Jews, particularly the intellectual and political elite, had fled the advancing German army into the Soviet-occupied eastern Poland and to the area of the future General Government in the hope of a Polish counter-attack, which never came. On 8 February 1940, the Germans ordered the Jewish residents to be limited to specific streets in the Old City and the adjacent Bałuty quarter, the areas that would become the ghetto. To expedite the relocation, the Orpo Police launched an assault known as “Bloody Thursday” in which 350 Jews were fatally shot in their homes, and outside, on 5–7 March 1940. Over the next two months, wooden and wire fences were erected around the area to cut it off from the rest of the city. Jews were formally sealed within the ghetto walls on 1 May 1940.

As nearly 25 percent of the Jews had fled the city by the time the ghetto was set up, its prisoner population as of 1 May 1940 was 164,000. Over the coming year, Jews from German-occupied Europe as far away as Luxembourg were deported to the ghetto on their way to the extermination camps. A small Romany population was also resettled there. By May 1, 1941, the population of the ghetto had reached 148,547.

Ghetto policing. To ensure no contact between the Jewish and non-Jewish populations of the city, two German Order Police formations were assigned to patrol the perimeter of the ghetto. Within the Ghetto, a Jewish Police force was created to ensure that no prisoners tried to escape. On 10 May 1940, orders went into effect prohibiting any commercial exchange between Jews and non-Jews in Łódź. By the new German decree, those caught outside the ghetto could be shot on sight. The contact with people who lived on the “Aryan” side was also impaired by the fact that Łódź had a 70,000-strong ethnic German minority loyal to the Nazis (the Volksdeutsche), making it impossible to bring food illegally. To keep outsiders out, rumours were also spread by Hitler’s propaganda saying that the Jews were the carriers of infectious diseases. For the week of 16–22 June 1941 (the week Nazi Germany launched Operation Barbarossa), the Jews reported 206 deaths and two shootings of women near the barbed wire.

In other ghettos throughout Poland, thriving underground economies based on the smuggling of food and manufactured goods developed between the ghettos and the outside world. In Łódź, however, this was practically impossible due to heavy security. The Jews were entirely dependent on the German authorities for food, medicine and other vital supplies. To exacerbate the situation, the only legal currency in the ghetto was a specially created ghetto currency. Faced with starvation, Jews traded their remaining possessions and savings for this scrip, thereby abetting the process by which they were dispossessed of their remaining belongings.

Chaim Rumkowski and the Jewish Council.

To organize the local population and maintain order, the German authorities established a Jewish Council, commonly referred to as the Judenrat or Ältestenrat (“Council of Elders”) in Łódź. The chairman of the Judenrat appointed by the Nazi administration was Chaim Rumkowski (age 62 in 1939). Even today, he is still considered one of the most controversial figures in the history of the Holocaust. Known mockingly as “King Chaim”, Rumkowski was granted unprecedented powers by the Nazi officials, which authorized him to take all necessary measures to maintain order in the Ghetto.

Directly responsible to the Nazi Amtsleiter Hans Biebow, Rumkowski adopted an autocratic style of leadership to transform the ghetto into an industrial base manufacturing war supplies. Convinced that Jewish productivity would ensure survival, he forced the population to work 12-hour days despite abysmally poor conditions and a lack of calories and protein, producing uniforms, garments, wood, metalwork, and electrical equipment for the German military. By 1943, some 95 percent of the adult population was employed in 117 workshops, which, Rumkowski once boasted to the mayor of Łódź, were a “gold mine.” It was possibly because of this productivity that the Łódź Ghetto managed to survive long after all the other ghettos in occupied Poland were liquidated. Rumkowski systematically singled out for expulsion his political opponents, or anyone who might have had the capacity to lead a resistance to the Nazis. Conditions were harsh, and the population was entirely dependent on the Germans. Typical intake, made available, averaged between 700 and 900 calories per day, about half the calories required for survival. People affiliated with Rumkowski received disproportionately larger deliveries of food, medicine, and other rationed necessities. Everywhere else, starvation was rampant, and diseases like tuberculosis were widespread, fueling dissatisfaction with Rumkowski’s administration, which led to a series of strikes in the factories. In most instances, Rumkowski relied on the Jewish police to quell the discontented workers, although at least in one example, the German Order Police was asked to intervene. Strikes usually erupted over the reduction of food rations.

Disease was a significant feature of ghetto life with which the Judenrat had to contend. Medical supplies were critically limited, and the ghetto was severely overcrowded. The entire population of 164,000 people was forced into an area of 4 square kilometres (1.5 square miles), of which 2.4 square kilometres (0.93 square miles) were developed and habitable. Fuel supplies were severely short, and people burned whatever they could to survive the Polish winter. Some 18,000 people in the ghetto are believed to have died during a famine in 1942, and altogether, about 43,800 people died in the ghetto from starvation and infectious disease.

Deportations. Overcrowding in the ghetto was exacerbated by the influx of some 40,000 Polish Jews forced out from the surrounding Warthegau areas, as well as by the Holocaust transports of foreign Jews resettled to Łódź from Vienna, Berlin, Cologne, Hamburg and other cities in Nazi Germany, as well as from Luxembourg, and the Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia including the citywide Theresienstadt concentration camp. Heinrich Himmler visited the ghetto for the first time on 7 June 1941. On 29 July 1941, following an inspection, most patients of the ghetto’s psychiatric hospital were taken away, never to return. “They understood, for example, why they had been injected with tranquillizers in the night. Injections of scopolamine were used, at the request of the Nazi authorities.” Situated 50 kilometres (31 mi) north of Łódź in the town of Chełmno, the Kulmhof extermination camp began gassing operations on 8 December 1941. Two weeks later, on 20 December 1941, Rumkowski was ordered by the Germans to announce that 20,000 Jews from the ghetto would be deported to undisclosed camps, based on selection by the Judenrat. An Evacuation Committee was set up to help select the initial group of deportees from among those who were labelled ‘criminals’: people who refused to or who could not work, and people who took advantage of the refugees arriving in the ghetto to satisfy their own basic needs.

By the end of January 1942, some 10,000 Jews were deported to Chełmno (known as Kulmhof in German). The Chełmno extermination camp set up by SS-Sturmbannführer Herbert Lange served as a pilot project for the secretive Operation Reinhard, the deadliest phase of the “Final Solution”. In Chełmno, the inmates were killed with the exhaust fumes of moving gas vans. The stationary gas chambers had yet to be built at the death camps of Einsatz Reinhardt. By 2 April 1942, an additional 34,000 victims were sent there from the ghetto, with 11,000 more by 15 May 1942, and over 15,000 more by mid-September, for a total of an estimated 55,000 people. The Germans planned that children, older people, and anyone deemed “not fit for work” would follow them.