Syria – Desert (Palmyra) and East (Raqqah, Deir ez-Zor) November 9, 2019

Day 9 Palmyra, drive to Damascus

We left Homs at 9 and had a confusing visit to a nearby army base to pick up a military escort supposedly necessary to visit Palmyra. But that policy ended one month ago.

The 150km drive was through very flat terrain, all desert with some grass and low bush cover.

We passed convoys of soldiers in buses and Toyoto trucks with machine guns on the back. Checkpoints were more common and thorough. One had a large poster of Assad with Putin, a Lebanese Hizbollah leader.

PALMYRA

Palmyra is an ancient Semitic city in present-day Homs Governorate. Archaeological finds date back to the Neolithic period, and documents first mention the city in the early second millennium BC. Palmyra changed hands on a number of occasions between different empires before becoming a subject of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

The city grew wealthy from trade caravans; the Palmyrenes became renowned as merchants who established colonies along the Silk Road and operated throughout the Roman Empire. Palmyra’s wealth enabled the construction of monumental projects, such as the Great Colonnade, the Temple of Bel, and the distinctive tower tombs.

Ethnically, the Palmyrenes combined elements of Amorites, Arameans, and Arabs. The city’s social structure was tribal, and its inhabitants spoke Palmyrene (a dialect of Aramaic), while using Greek for commercial and diplomatic purposes. Greco-Roman culture influenced the culture of Palmyra, which produced distinctive art and architecture that combined eastern and western traditions. The city’s inhabitants worshiped local Semitic deities, Mesopotamian and Arab gods.

By the third century AD Palmyra had become a prosperous regional center. It reached the apex of its power in the 260s, when the Palmyrene King Odaenathus defeated Persian Emperor Shapur I. The king was succeeded by regent Queen Zenobia, who rebelled against Rome and established the Palmyrene Empire. In 273, Roman emperor Aurelian destroyed the city, which was later restored by Diocletian at a reduced size. The Palmyrenes converted to Christianity during the fourth century and to Islam in the centuries following the conquest by the 7th-century Rashidun Caliphate, after which the Palmyrene and Greek languages were replaced by Arabic.

Before AD 273, Palmyra enjoyed autonomy and was attached to the Roman province of Syria, having its political organization influenced by the Greek city-state model during the first two centuries AD. The city became a Roman colonia during the third century, leading to the incorporation of Roman governing institutions, before becoming a monarchy in 260. Following its destruction in 273, Palmyra became a minor center under the Byzantines and later empires. Its destruction by the Timurids in 1400 reduced it to a small village. Under French Mandatory rule in 1932, the inhabitants were moved into the new village of Tadmur, and the ancient site became available for excavations. During the Syrian Civil War in 2015, the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) destroyed large parts of the ancient city, which was recaptured by the Syrian Army on 2 March 2017.

Location. Palmyra lies 215 km (134 mi) northeast of the Syrian capital, Damascus, in an oasis surrounded by palms (of which twenty varieties have been reported). Two mountain ranges overlook the city; the northern Palmyrene mountain belt from the north and the southern Palmyrene mountains from the southwest. In the south and the east Palmyra is exposed to the Syrian Desert. A small wadi (al-Qubur) crosses the area, flowing from the western hills past the city before disappearing in the eastern gardens of the oasis. South of the wadi is a spring, Efqa. Pliny the Elder described the town in the 70s AD as famous for its desert location, the richness of its soil, and the springs surrounding it, which made agriculture and herding possible.

Palmyra began as a small settlement near the Efqa spring on the southern bank of Wadi al-Qubur. Most of the city’s monumental projects were built on the wadi’s northern bank.

The Walls of Palmyra started in the first century as a protective wall containing gaps where the surrounding mountains formed natural barriers; it encompassed the residential areas, the gardens and the oasis. After 273, Aurelian erected the rampart known as the wall of Diocletian; it enclosed about 80 hectares, a much smaller area than the original pre-273 city. Little of the walls remain.

Cemeteries. West of the ancient walls, the Palmyrenes built a number of large-scale funerary monuments which now form the Valley of Tombs, a 1-kilometre-long (0.62 mi) necropolis. The more than 50 monuments were primarily tower-shaped and up to four stories high. Towers were replaced by funerary temples in the first half of the second century AD, as the most recent tower is dated to AD 128. The city had other cemeteries in the north, southwest and southeast, where the tombs are primarily hypogea (underground). The Palmyrenes buried their dead in elaborate family mausoleums, most with interior walls forming rows of burial chambers (loculi) in which the dead, laying at full length, were placed. A bust relief of the person interred formed part of the wall’s decoration, acting as a headstone and sealing the openings of the burial chambers. The reliefs emphasized clothing, jewelry and a frontal representation of the person depicted. Palmyrene bust reliefs, unlike Roman sculptures, are rudimentary portraits; although many reflect high quality individuality, the majority vary little across figures of similar age and gender. Many surviving funerary busts reached Western museums during the 19th century.

Sarcophagi appeared in the late second century and were used in some of the tombs. Many burial monuments contained mummies embalmed in a method similar to that used in Ancient Egypt.

Citadel of Palmyra. This 12th century castle sits on the top of the mountain to the west of the modern town.

PALMYRA TOWN (Tadmur). Palmyra is the administrative centre of the Tadmur District. Prior to the war in 2004, the city had a population of 51,323 and the subdistrict a population of 55,062. Tadmur’s inhabitants were recorded to be Sunni Muslims in 1838.

During the Syrian Civil War, the city’s population significantly increased due to the influx of internally displaced refugees from other parts of the country.

On 13 May 2015, the militant organization ISIS launched an attack on the modern town, taking only 5 days to capture the city, with their forces entering the area of the World Heritage Site several days later.

In May and June, ISIL destroyed the tomb of Mohammed bin Ali (a descendant of the Islamic prophet Muhammad’s cousin Ali, and a site revered by Shia Muslims – Mohammed bin Ali’s tomb was located in a mountainous region 5kms north of Palmyra), and the tomb of Nizar Abu Bahaaeddine (a Sufi scholar who lived in Palmyra in the 16th century. Abu Bahaaeddine’s tomb was situated in an oasis about 500m from Palmyra’s main ancient ruins).

ISIL also destroyed a number of tombstones at a local cemetery for Palmyra’s residents. ISIL is also reported to have placed explosives around Palmyra.

In March 2016 a large-scale offensive by the SAA (supported by Hezbollah and Russian airstrikes) initially regained the areas south and west of the city. After capturing the orchards and the area north of the city, the assault on the city began. In the early morning hours of the 27th of March 2016, the Syrian military forces regained full control over the city. In December 2016, ISIS retook the oilfields outside of the city, and began moving back into the city center.

On 1 March 2017, the Syrian army backed by warplanes, had entered to Palmyra and captured the western and northern western sections of the city amid information about pulling back by ISIS from the city. The next day, the Syrian Army recaptured the entire city of Palmyra, after ISIL fully withdrew from the city.

When we drove the city on November 9th, it was almost completely destroyed. I didn’t see an undamaged building. A few shops had opened in some of the bottom floors of a few of the damaged buildings. A few residents were in the main street but the rest was completely abandoned.

Museum of Palmyra. ISIS also occupied this basically destroying everything inside. The valuable funerary busts had all been removed and sent to Damascu. But all larger stone statues were left. ISIS had destroyed the faces and hands or broken off the heads of all the statues. All the glass display cases and the great model of the city were destroyed. There were 3 mosaics on the walls that appeared intact. Two wonderful stone reliefs were in the museum, both recovered at the Syrian/Turkey border on their way to being sold by ISIS.

Zenokia Cham Palace Hotel. Built in the early 20th century, this great hotel stands on the edge of the WHS. It was occupied by ISIS – all the furniture, interior doors, bathrooms and everything inside was gone. Plaster moldings and anything on the walls were on floor.

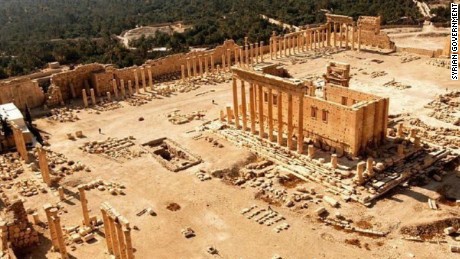

PALMYRA World Heritage Site

The site is huge with a sea of columns. All the hundreds of columns had a stone platform projected from the column at about 5m above ground. Each held a statue of a prominent god or citizen of the city but I only saw one statue remaining. Some had an inscription under the platform describing the dignitary.

TEMPLE OF BEL (Baal)

History. The temple was built on a small rise that shows signs of human occupation that goes back to the third millennium BC. The area was occupied in pre-Roman periods with a former temple that is usually referred to as “the first temple of Bel” and “the Hellenistic temple”. The walls of the temenos and propylaea were constructed in the late first and the first half of the second century AD.

The Temple of Bel was converted into a Christian church during the Byzantine Era. Parts of the structure were modified by Arabs in 1132 which preserved the structure and converted the Temple into a mosque. The enormous temple courtyard (approx. 200 x 200 meters) held mud-brick houses among the ruins, and served as a fortified citadel for the village of Palmyra (known as Tadmur during the 1100s). The mosque in the temple proper and the dwellings remained in use until the 1920s when Franco-Syrian archaeological missions cleared the temple grounds of its postclassical elements. Most of the Corinthian columns of the inner colonnades still showed pedestals where the statues of the benefactors stood. The temple was aligned along the eastern end of the Great Colonnade at Palmyra.

Architecture. The temple showed a remarkable synthesis of ancient Near Eastern and Greco-Roman architecture. The temple remains lay inside a large precinct lined by porticos. It had a rectangular shape and was oriented north-south. It was based on a paved court surrounded by a massive 205-metre (673 ft) long wall with a propylaeum. On a podium in the middle of the court was the actual temple building. The cella was entirely surrounded by a prostyle of Corinthian columns, only interrupted on the long side by an entrance gate with large steps leading from the court. The cella was unique in the fact that it had two inner sanctuaries, the north and south adytons, dedicated as the shrines of Bel and other local deities. The northern chamber was known for a bas-relief carving of the seven planets known to the ancients surrounded by the twelve signs of the Zodiac and the carvings of a procession of camels and veiled women. The cella was lit by two pairs of windows cut high in the two long walls. In three corners of the building stairwells could be found that led up to rooftop terraces.

In the court there were the remains of a basin, an altar, a dining hall, and a building with niches. And in the northwest corner lay a ramp along which sacrificial animals were led into the temple area. There were three monumental gateways, of which the entry was through the west gate.

Before the war and destruction by ISIS – all but the front portal are totally destroyed.  Syrian Civil War and Destruction by ISIS. Syria’s Director of Antiquities Maamoun Abdul Karim stated that ISIL was looking for treasures and “stores of gold” in the city. On 30 August 2015, the Associated Press reported that ISIL had partially demolished the temple by explosives, citing eyewitness accounts. The bricks and columns were reported as lying on the ground.

Syrian Civil War and Destruction by ISIS. Syria’s Director of Antiquities Maamoun Abdul Karim stated that ISIL was looking for treasures and “stores of gold” in the city. On 30 August 2015, the Associated Press reported that ISIL had partially demolished the temple by explosives, citing eyewitness accounts. The bricks and columns were reported as lying on the ground.

The main entrance arch survived the destruction of the temple. The Institute for Digital Archaeology proposed that replicas of this arch be installed in Trafalgar Square, London and Times Square, New York City. It was later decided that instead of the temple’s main entrance, the replica would be of part of the Monumental Arch.

Following the recapture of Palmyra by the Syrian Army in March 2016, director of antiquities Maamoun Abdelkarim stated that the Temple of Bel, along with the Temple of Baalshamin and the Monumental Arch, will be rebuilt using the surviving remains. ISIL recaptured the city on 11 December, but the Syrian Army retook it on 2 March 2017.

My Experience. This was the highlight of Palmyra, one of the most intact temples in the world. A grand double row of columns with a roof stood inside the exterior wall. All of the roof and most of the outside row of columns were destroyed by ISIS.

On 23 May 2015 ISIL militants destroyed the Lion of Al-lāt and other statues; this came days after the militants had gathered the citizens and promised not to destroy the city’s monuments. ISIL destroyed the Temple of Baalshamin on 23 August 2015.

The magnificent cella of the Temple of Bel stood on a podium in the middle of the enclosure. On 30 August 2015, it was dynamited using 12 tons of explosive and now is a mass of fractured rock, except for the front portal that is damaged but still standing. On 30 August 2015, ISIL destroyed the cella of the Temple of Bel. The temple’s exterior walls and entrance arch remain.

Great Colonnade (Cardo Maximus) was Palmyra’s 1.1-kilometre-long (0.68 mi) main street., which extended from the Temple of Bel in the east, to the Funerary Temple no.86 in the city’s western part. It had a monumental arch in its eastern section where the street makes a 32º angle turn. That magnificent arch was destroyed by ISIS. The tetrapylon stands in the center. Most of the columns date to the second century AD and each is 9.50 metres (31.2 ft) high.

The arches are no more, the side columns still stand.

Tetrapylon was erected during the renovations of Diocletian at the end of the third century. It sits in the middle of the Cardo Maximus, serving as the central “square” of the street. The other main street crosses at the Tetrapylon.

Tetrapylon was erected during the renovations of Diocletian at the end of the third century. It sits in the middle of the Cardo Maximus, serving as the central “square” of the street. The other main street crosses at the Tetrapylon.

Only 4 columns are still standing

It is a square platform and each corner contains a grouping of four columns. Each column group supports a 150 tons cornice and contains a pedestal in its center that originally carried a statue. Out of sixteen columns, only one is original while the rest are from reconstruction in 1963, using concrete. The original columns were brought from Egypt and carved out of pink granite.

This was almost totally destroyed by ISIS. Only 4 concrete columns remain.

Funerary Temple no.86 (House Tomb) is located at the western end of the Great Colonnade. It was built in the third century AD and has a portico of six columns and vine patterns carvings. Inside the chamber, steps leads down to a vault crypt. The shrine might have been connected to the royal family as it is the only tomb inside the city’s walls.

The Baths of Diocletian were on the left side of the colonnade. Nearby were residences, the Temple of Baalshamin, and the Byzantine churches, which include “Basilica IV”, Palmyra’s largest church. The church is dated to the Justinian age, its columns are estimated to be 7 metres (23 ft) high, and its base measured 27.5 by 47.5 metres (90 by 156 ft).

The Temple of Nabu and the Roman theater were built on the colonnade’s southern side. Behind the theater were a small senate building and the large Agora, with the remains of a triclinium (banquet room) and the Tariff Court. A cross street at the western end of the colonnade leads to the Camp of Diocletian, built by Sosianus Hierocles (the Roman governor of Syria). Nearby are the Temple of Al-lāt and the Damascus Gate.

Baths of Diocletian. Sitting on the Cardio Maximus, much are ruined and do not survive above the level of the foundations. The complex’s entrance is marked by four massive Egyptian granite columns each 1.3 metres (4 ft 3 in) in diameter, 12.5 metres (41 ft) high and weigh 20 tonnes. Inside, the outline of a bathing pool surrounded by a colonnade of Corinthian columns is still visible in addition to an octagonal room that served as a dressing room containing a drain in its center. Sossianus Hierocles, a governor under Emperor Diocletian, claimed to have built the baths, but the building was probably erected in the late second century and Sossianus Hierocles renovated it.

Theatre. The seats, the lower tier of the stage with its great columns and the orchestra pit with its surround 1m high semi-circular wall are still intact. The theatre sits in the middle of a grand round square once lined by columns and arcaded shops. ![]() Senate building is largely ruined. It is a small building that consists of a peristyle courtyard and a chamber that has an apse at one end and rows of seats around it.

Senate building is largely ruined. It is a small building that consists of a peristyle courtyard and a chamber that has an apse at one end and rows of seats around it.

Agora of Palmyra is part of a complex that also includes the tariff court and the triclinium, built in the second half of the first century AD. The agora is a massive 71 by 84 metres (233 by 276 ft) structure with 11 entrances. Inside the agora, 200 columnar bases that used to hold statues of prominent citizens were found. The inscriptions on the bases allowed an understanding of the order by which the statues were grouped; the eastern side was reserved for senators, the northern side for Palmyrene officials, the western side for soldiers and the southern side for caravan chiefs. Unlike the Greek Agoras (public gathering places shared with public buildings), Palmyra’s agora resembled an Eastern caravanserai more than a hub of public life.

Triclinium of the Agora is located to the northwestern corner of the Agora and can host up to 40 person. It is a small 12 by 15 metres (39 by 49 ft) hall decorated with Greek key motifs that run in a continuous line halfway up the wall. The building was probably used by the rulers of the city as a triclinium or banqueting hall.

Tariff Court is a large rectangular enclosure south of the agora and sharing its northern wall with it. Originally, the entrance of the court was a massive vestibule in its southwestern wall. However, the entrance was blocked by the construction of a defensive wall and the court was entered through three doors from the Agora. The court gained its name by containing a 5 meters long stone slab that had the Palmyrene tax law inscribed on it.

The following temples stand to the south and west of Cardo Maximus. I didn’t visit any of them.

Temple of Baalshamin dates to the late 2nd century BC in its earliest phases; its altar was built in AD 115, and it was substantially rebuilt in AD 131. It consisted of a central cella and two colonnaded courtyards north and south of the central structure. A vestibule consisting of six columns preceded the cella which had its side walls decorated with pilasters in Corinthian order.

Temple of Nabu is largely ruined. The temple was Eastern in its plan; the outer enclosure’s propylaea led to a 20 by 9 metres (66 by 30 ft) podium through a portico of which the bases of the columns survives. The peristyle cella opened onto an outdoor altar.

Temple of Al-lāt is largely ruined with only a podium, a few columns and the door frame remaining. Inside the compound, a giant lion relief (Lion of Al-lāt) was excavated and in its original form, was a relief protruding from the temple compound’s wall.

The ruined Temple of Baal-hamon was located on the top of Jabal al-Muntar hill and oversees the spring of Efqa. Constructed in AD 89, it consisted of a cella and a vestibule with two columns. The temple had a defensive tower attached to it; a mosaic depicting the sanctuary was excavated and it revealed that both the cella and the vestibule were decorated with merlons.

DESTRUCTION by ISIS

On 23 May 2015 ISIL militants destroyed the Lion of Al-lāt and other statues; this came days after the militants had gathered the citizens and promised not to destroy the city’s monuments. ISIL destroyed the Temple of Baalshamin on 23 August 2015. On 30 August 2015, ISIL destroyed the cella of the Temple of Bel. The temple’s exterior walls and entrance arch remain.

On 4 September 2015, ISIL destroyed three of the best preserved tower tombs including the Tower of Elahbel. On 5 October 2015, news media reported that ISIL was destroying buildings with no religious meaning, including the monumental arch. On 20 January 2017, news emerged that the militants had destroyed the tetrapylon and part of the theater. Following the March 2017 capture of Palmyra by the Syrian Army, Maamoun Abdulkarim, director of antiquities and museums at the Syrian Ministry of Culture, stated that the damage to ancient monuments may be lesser than earlier believed and preliminary pictures showed almost no further damage than what was already known. Antiquities official Wael Hafyan stated that the Tetrapylon was badly damaged while the damage to the facade of the Roman theatre was less serious.

Restoration. In response to the destruction, on 21 October 2015, Creative Commons started the New Palmyra project, an online repository of three-dimensional models representing the city’s monuments; the models were generated from images gathered, and released into the public domain. Consultations with the UNESCO, UN specialized agencies, archaeological associations and museums produced plans to restore Palmyra; the work is postponed until the violence in Syria ends as many international partners fear for the safety of their teams as well as ensuring that the restored artifacts will not be damaged again by further battles. Minor restorations took place; two Palmyrene funerary busts, damaged and defaced by ISIL, were sent off to Rome where they were restored and sent back to Syria. The restoration of the Lion of Al-lāt took two months and the statue was displayed on 1 October 2017; it will remain in the National Museum of Damascus.

The archaeological site of Palmyra is a vast field of ruins and only 20–30% of it is seriously damaged. Unfortunately these included important parts, such as the Temple of Bel, while the Arc of Triumph can be rebuilt.” He added: “In any case, by using both traditional methods and advanced technologies, it might be possible to restore 98% of the site”. Restoration is underway, with the ancient city ready to receive tourists in summer 2019.

Syrian Civil War. In the war, Palmyra experienced widespread looting and damage by combatants. In 2013, the façade of the Temple of Bel sustained a large hole from mortar fire, and colonnade columns were damaged by shrapnel. The Syrian Army positioned its troops in some archaeological-site areas, while Syrian opposition fighters positioned themselves in gardens around the city.

On 13 May 2015, ISIL launched an attack on the modern town of Tadmur, and some artifacts were transported from the Palmyra museum to Damascus for safekeeping; a number of Greco-Roman busts, jewelry, and other objects looted from the museum have been found on the international market. ISIL forces entered Palmyra and the the Syrian air force bombed the site on 13 June, damaging the northern wall close to the Temple of Baalshamin. During ISIL’s occupation of the site, Palmyra’s theatre was used as a place of public executions of their opponents and captives. On 18 August, Palmyra’s retired antiquities chief Khaled al-Asaad was beheaded by ISIL after being tortured for a month to extract information about the city and its treasures; al-Asaad refused to give any information to his captors.

Syrian government forces supported by Russian airstrikes recaptured Palmyra on 27 March 2016. According to initial reports, the damage to the archaeological site was less extensive than anticipated, with numerous structures still standing. De-mining teams began clearing mines. Following heavy fighting, ISIL briefly reoccupied the city on 11 December 2016 and Syrian Army retook the city on 2 March 2017.

It was then a long 350km drive back to Damascus on November 9. I stayed in the same wonderful hotel as I originally stayed in. In the morning it was a 3-hour drive to Beirut to catch my flight to Ankara Turkey and my van. I was missing her – it has been one whole month of tours.

Syria – Desert (Palmyra) and East (Raqqah, Deir ez-Zor)

NOMAD MANIA Syria – Desert (Palmyra) and East (Raqqah, Deir ez-Zor)

World Heritage Sites

Crac des Chevaliers and Qal’at Salah El-Din

Site of Palmyra

Tentative WHS

Dura Europos (08/06/1999)

Mari & Europos-Dura sites of Euphrates Valley (23/06/2011)

Mari (Tell Hariri) (08/06/1999)

Raqqa-Ràfiqa : la cité abbasside (08/06/1999)

Un Château du désert : Qasr al-Hayr ach-Charqi (08/06/1999)

XL

Al Hasakah province extreme northeast (Al Malikiyah)

Ceylanpinar/Ras al Ayn

Religious Temples: Dura-Europos: Dura-Europos Church

Cities of Asia and Oceania

DEIR EZ-ZOR

HASAKAH

QAMISHLI

HOMS World City and Popular Town

Religious Temples: Khalid ibn Al-Walid Mosque

RAQQA

Tentative WHS: Raqqa-Ràfiqa : la cité abbasside (08/06/1999)

Religious Temples: Great Mosque