Naples March 9-10 2019

TIPS for NAPLES

1. Parking. This is a driving and especially parking nightmare. It seems that everyone has a car, can only park on the street and use every available niche with little attention to rules. Double and sometimes triple parking is routine. Add in narrow streets, pedestrians and motorcycles and you get a mess. I made the mistake of trying to find parking and drove around for an hour, finally parking near the archaeology museum on the sidewalk. Amazingly when I returned 6 hours later, there was no ticket and it wasn’t towed.

Find parking at a nearby train or metro station at the end of a line and use public transport.

2. Naples Pass. Gives 10 days of free admissions to public museums and free public transportation. €19 for a single adult. When I was there, it was the end of a week of free museums in most of Italy so I did not buy.

3. Napoli style pizza. World famous, I think you might be a little disappointed. Napoli style pizza has a soft crust and the rest is average. Go to the north of Italy for crispy crust. I make better at home.

I started driving at 6:30 and saw the following places in order:

Underwater Archaeological Park of Baia. Well west of Naples, this is a dive site that explores an ancient Roman villa with some mosaic floors. Dives are €40 plus €20 for equipment rental and are quite shallow, most at 5m and one descent to 13m. I didn’t do this.

BRADYSEISM in the Flegrea Area. Bradyseism it the gradual uplift or descent of part of the earth’s surface caused by the filling or emptying of an underground magma chamber and/or hydrothermal activity, particularly in the volcanic calderas.

The Campania region has three large volcanic areas: Vesuvius, Ischia and Campi Flegrei. Campi Flegrei, 15kms west of Vesuvius, is a series of hills with a maximum elevation of 460m above sea level. It is one of the ten super volcanoes in the world known for soil lifting, called bradyseism.

The town of Pozzuoli, just west of Naples, is often affected – between 1982-84, a seismic crisis brought down the entire area causing the evacuation of thousands of people. Until 1983, the pillars of the Temple of Serapis, which had been partially submerged by the sea, are now above sea level. The three 6.30m marble columns of the temple are one of the best measures of Bradyseism.

The Solfatara of Pozzuoli, one of 40 volcanoes that make up Campi Flegrea is 3kms south of the city centre. It has been inactive for about 2000 years but produces 160° sulfur vapors, CO2 and boiling mud volcanoes. The Island of Ischia has the 1841 Vesuvius Observatory, the oldest volcano observatory in the world. This is a tentative World Heritage Site (01/06/2006)

I drove into Pozzuoli, a city on the water. The Temple of Serapis is just a hundred metres from the ocean. It is well below street level and consists of a circular temple surrounded by a square of columns, three of which are quite high. The bottom was dry.

NAPLES

Castel dell’Ovo. Sitting on the water, it is accessed by a narrow causeway.

Naples Centrale Train Station. I made a quick detour here to purchase my Naples Pass to find out museums were free the whole week. A great deal as includes public transportation.

Museo di Capodimonte. This modern art museum is high above next to a park.

I then drove around for an hour trying to find parking and ended up parking well up on a sidewalk on a side street one block from the archaeology museum (and didn’t get a ticket or towed).

National Archaeological Museum. Unexpectantly closed (they had some sort of emergency water problem), I returned at 5 pm and it was open. Start with a lot of sculpture, most part of the Farnese collection – especially good are the huge Hercules and the Bull. The Farnese gem’s highlight is the Farnese cup, a bowl carved from a single piece of agate – the carved inside utilizes a white layer of the agate. After the usual Roman glass and brass (all in Italian), see the huge model of Pompeii followed by several rooms of the art removed from the city – the Romans were not great artists.

As per my usual routine, I picked my itinerary starting at the most distant bookmark. One thing Google Maps does not do is show elevation change.

Museo Nazionale di San Martino. Beware this fort is a huge climb up endless stairs to the top of the mountain. The museum has some big galleys but is mostly religious art (very tiring). The church with its huge cloister is another magnificent site. The many rooms lined with wood paneling, wood inlays and ‘seats’ were as good as they get. The church is an over-the-top marble fantasy.

The main reason to come up here is easily the best views in the city and a great place to get semi-orientated. The church and priory have multiple viewpoints.

I then had a long descent mostly following roads and the myriad narrow lanes of the old part of Naples. The narrow lanes are paved with large black pavers.

Basilica Real de San Francesco da Paola. This white marble monster with its semi-circular colonnade takes up the entire south side of a huge plaza surrounded by two palaces. It is a large round church with a huge dome and another marble fantasy.

Via Toledo. The most popular street in Naples starts at the west end of the plaza. The first several blocks are pedestrianized and were mobbed with people on a Saturday afternoon. It has all the usual stores, restaurants, ice cream and pastry stores.

Palazzo Zevallos Stigliano. On Via Toledo, this magnificent palace contains the Gallery d’Italy with mostly Renaissance Campania artists but a few Rubens, Van Dyck and Riberia pieces. The highlight is the building, constructed in 1536 to attract residences of the most prominent of the noble families. Purchased by Vandeneyden, a Flemish family, the core of the art here dates from their collection. The palace had successive owners and restorations. The 3 floors of the gallery surround a wonderful hall with a stained glass ceiling. Private €5

Toledo Metro Station. Toledo is a station on Line 1 of the Naples Metro, named after nearby Via Toledo. It won the 2013 LEAF Award as “Public building of the year”.

Chiesa del Gesu Nuova. Has a spectacular marble interior.

San Domenico Maggiore. Enter a small round portico and unusually climb stairs to get up to the church. This is more austere than most of the churches. The museum (€5) has 56 Aragonese coffins, sacristy, and furnishings.

San Gennaro Cathedral. Dedicated to San Gennaro, an early Christian martyred in 306 AD, the crypt has his relics. The altarpiece is wonderful with a stained glass halo surround Mary. Baptistry €2

Santa Chiara (Cathedral Santa Maria Assunta).

Lanificio 25. If you find this place, you get your ‘explorers’ badge. Beside another church, the entrance to this derelict residential square is an ancient stone gate with Lanificiao across the top. Go to the far right corner to a passage that dead-ends in a small open area. This is a small music venue called the Carlo Rendan Association open on Tuesdays to Fridays from 3-7 pm. (phone # 328-748 5836)

Palazzo Donnaregina (Contemporary Art Museum). Another modern art museum full of pieces of dubious value – and you have to walk up a lot of stairs to see this junk.

MUSA – University Museum of Arts and Sciences. The main museum houses the “Antomia Umana” (human anatomy) section, mostly redundant information for me. Probably not worth the walk to get here.

I then escaped Naples and drove south towards Pompeii.

I had Napoli-style pizza and after found out that crispy crust pizza is from the north of Italy and soft crust is from Naples. I make it better at home: can get the crust just right, use more flavourful sauce and put on the ingredients I like. But the price was right at €4.50 for a large pizza.

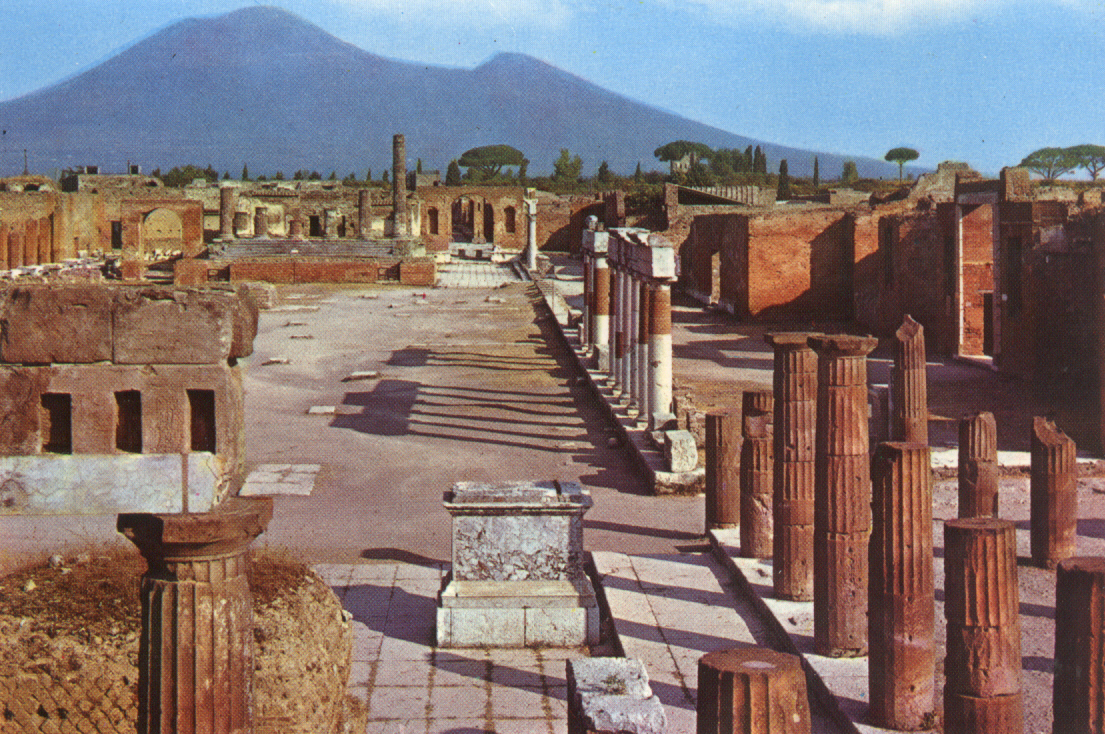

POMPEII

I was up early and the first person at the archaeological park when it opened at 8:30. The week of free museums throughout Italy ended on the day I was there avoiding the €15 admission price. However the crowds appeared soon after – most seem to be orientals on tours.

I entered at the southeast corner near the amphitheater, the newest part of Pompei. First pass a semi-circular glass pavilion with several of the plaster casts of bodies.

The amphitheater was originally outside the walls to accommodate crowds of up to 20,000. There are few seats remaining. Next to it is a very good Etruscan Museum that describes the first inhabitants of the Pompei area. This part of Pompei has mostly ruined walls with the “houses” gated off and not accessible. All the interior and exterior walls were once plastered and painted with frescoes. These are absent in this part. There are also no artifacts to see other than in the Naples Archaeology Museum and in the museum at the west entrance.

The streets are paved with large stones. Pedestrians used the blocks in the road to cross the street without having to step onto the road, which doubled up as Pompeii’s drainage and sewage disposal system. The spaces between the blocks let vehicles pass along the road, many with surprisingly deep cart tracks.

Some of the highlights for me were the Temple of Isis (unearthed in 1764-76, it brought early fame to Pompei), all the large stone fountains, the baths with their intact decorated roof, and the House of Venus in the Skull with its original pool and great well-preserved frescoes.

The Archaeological Areas of Pompei, Herculaneum and Torre Annunziata are justifiably a World Heritage Site and is one of the most popular tourist attractions in Italy, with approximately 2.5 million visitors every year.

Pompeii was an ancient Roman city near modern Naples. Pompeii, along with Herculaneum and many villas in the surrounding area (e.g. at Boscoreale, Stabiae), was buried under 4 to 6 m of volcanic ash and pumice in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. Volcanic ash typically buried inhabitants who did not escape the lethal effects of the earthquake and eruption.

Largely preserved under the ash, the excavated city offers a unique snapshot of Roman life, frozen at the moment it was buried and providing an extraordinarily detailed insight into the everyday life of its inhabitants. Organic remains, including wooden objects and human bodies, were entombed in the ash and decayed away, making natural molds; and excavators used these to make plaster casts, unique and often gruesome figures from the last minutes of the catastrophe. The numerous graffiti carved on the walls and inside rooms provides a wealth of examples of the largely lost Vulgar Latin spoken colloquially, contrasting with the formal language of the classical writers.

Excavations recommenced in several unexplored areas of the city, and in 2018 new discoveries were reported.

Geography. The ruins of Pompeii are located near the modern town of Pompei and about 8 km away from Mount Vesuvius. It stands on a spur about 40 m above sea level formed by an ancient lava flow to the north of the mouth of the Sarno River (known in ancient times as the Sarnus). Three sheets of sediment from large landslides lie on top of the lava, perhaps triggered by extended rainfall.

Today, Pompeii is some distance inland, but in ancient times it overlooked the coast and had a port. It covered a total of 64 to 67 hectares (170 acres) and was home to 11,000 to 11,500 people, on the basis of household counts.

History

Early history. The first stable settlements on the site date back to the 8th century BC when the Oscans, a people of central Italy, founded five villages in the area. With the arrival of the Greeks in Campania from around 740 BC, Greek and Phoenician sailors used the location as a safe port.

Around the 6th century BC, it merged into a single community. 524 BC saw the arrival and settlement of the Etruscans in the area and Pompeii became a member of the Etruscan League of cities. In 474 BC the Greek city of Cumda, allied with Syracuse, conquered the Etruscans definitively at the Battle of Cumae and gained control of the area.

The Samnite period. From 450–375 BC witnessed large areas of the city being abandoned. The Samnites from the areas of Abruzzo and Molise, reinforced the city walls, that formed the basis for the currently visible walls.

From 343 BC the first Roman army entered the Campanian plain, and Pompeii continued to flourish due to the production and trade of wine and oil with places like Provence and Spain, as well as to intensive agriculture on farms around the city.

In the 2nd century BC, Pompeii enriched itself by taking part in Rome’s conquest of the east and it expanded to its ultimate limits. The forum and many public and private buildings of high architectural quality were built, including the large theatre, the sanctuary to Jupiter, the Basilica, the Comitium, the Stabian baths and a new two-story portico.

The Roman Period. Pompeii took part in the Social Wars that the towns of Campania initiated against Rome, but in 89 BC, Pompeii was forced to surrender and it became a Roman colony with the name of Colonia Cornelia Veneria Pompeianorum. The town became an important passage for goods that arrived by sea and had to be sent toward Rome or southern Italy along the nearby Appian Way. From c. 20 BC, Pompeii was fed with water by a spur from the Serino.

AD 62–79. The inhabitants of Pompeii had long been used to minor earthquakes, but on 5 February 62, a severe earthquake did considerable damage around the bay, and particularly to Pompeii. Chaos followed the earthquake. Fires, caused by oil lamps that had fallen during the quake, added to the panic. Temples, houses, bridges, and roads were destroyed and almost all buildings in the city were affected. In the days after the earthquake, anarchy ruled the city, where theft and starvation plagued the survivors. In the time between 62 and the eruption in 79, some rebuilding was done, but some of the damage had still not been repaired at the time of the eruption.

Eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79. The area had a substantial population, which had grown prosperous from the region’s renowned agricultural fertility. The heat was the main cause of death of people, previously believed to have died by ash suffocation. 250 °C (482 °F) hot surges (known as pyroclastic flows) at a distance of 10 kilometres (6 miles) from the vent was sufficient to cause instant death, even if people were sheltered within buildings. The people and buildings of Pompeii were covered in up to 12 different layers of tephra, in total 25 metres (82.0 ft) deep, which rained down for about six hours.

Rediscovery. Soon after the burial of the city, some survivors or thieves came to salvage valuables, including marble statues from buildings. Herculaneum was properly rediscovered in 1738 and Pompeii in 1748. During early excavations of the site, occasional voids in the ash layer had been found that contained human remains. Fiorelli realised these were spaces left by the decomposed bodies and so devised the technique of injecting plaster into them to recreate the forms of Vesuvius’s victims. This technique is still in use today, with a clear resin now used instead of plaster

The discovery of erotic art in Pompeii and Herculaneum left the archaeologists with a dilemma – between the mores of sexuality in ancient Rome and in Counter-Reformation Europe lay a clash of cultures.

A large number of artifacts from the buried cities are preserved in the Naples National Archaeological Museum. In 1819, the Pompeii exhibition was locked away in a so-called “secret cabinet” (gabinetto segreto), a gallery within the museum accessible only to “people of mature age and respected morals”. Re-opened, closed, re-opened again and then closed again for nearly 100 years, the Naples “Secret Museum” was briefly made accessible again at the end of the 1960s (the time of the sexual revolution) and was finally re-opened for viewing in 2000.

Roman city development. Under the Romans, Pompeii underwent a vast process of urban development, especially in the Augustan period. Public buildings include an amphitheatre, a palaestra with a central natatorium (cella natatoria) or swimming pool and an aqueduct that provided water for more than 25 street fountains, at least four public baths, and a large number of private houses (domūs) and businesses. The amphitheatre has been cited by modern scholars as a model of sophisticated design, particularly in the area of crowd control.

Besides the forum, many other service areas were found: the Macellumd (great food market), the Pistrinum (mill), the Thermopolium (a fast food place that served hot and cold dishes and beverages), and cauponae (cafes or ‘dives’ with a bad reputation as a hang out for thieves and prostitution services). An amphitheatre and two theatres have been found, along with a palaestra or gymnasium. A hotel (of 1,000 square metres) was found a short distance from the town; it is now nicknamed the “Grand Hotel Murecine”. Geothermal energy supplied channeled district heating for baths and houses. At least one building, the Lupanar, was dedicated to prostitution.

Modern archaeologists have excavated garden sites and urban domains to reveal the agricultural staples in Pompeii’s economy. Pompeii was fortunate to have a fruitful, fertile region of soil for harvesting a variety of crops. The soils surrounding Mount Vesuvius preceding its eruption have been revealed to have good water-holding capabilities, implying access to productive agriculture. The Tyrrhenian Sea’s airflow provided hydration to the soil despite the hot, dry climate. Barley, wheat, and millet were all produced along with wine and olive oil, in abundance for export to other regions.

Carbonised food plant remains, roots, seeds and pollens revealed that emmer wheat, Italian millet, common millet, walnuts, pine nuts, chestnuts, hazelnuts, chickpeas, bitter vetch, broad beans, olives, figs, pears, onions, garlic, peaches, carob, grapes, and dates were consumed. All except the dates could have been produced locally.

Tourism. Pompeii has been a popular tourist destination for over 250 years; it was on the Grand Tour. By 2008, it was attracting almost 2.6 million visitors per year, making it one of the most popular tourist sites in Italy. It is part of a larger Vesuvius National Park and was declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1997.

Pompeii is also a driving force behind the economy of the nearby town of Pompei. Many residents are employed in the tourism and hospitality business, serving as taxi or bus drivers, waiters or hotel operators.

Excavations in the site have generally ceased due to the moratorium imposed by the superintendent of the site. Additionally, the site is generally less accessible to tourists, with less than a third of all buildings open in the 1960s being available for public viewing today.

Conservation. Objects buried beneath Pompeii were well-preserved for almost 2,000 years. The lack of air and moisture let objects remain underground with little to no deterioration. Once excavated, the site provided a wealth of source material and evidence for analysis, giving detail into the lives of the Pompeiians.

Weathering, erosion, light exposure, water damage, poor methods of excavation and reconstruction, introduced plants and animals, tourism, vandalism and theft have all damaged the site in some way. Two-thirds of the city has been excavated, but the remnants of the city are rapidly deteriorating. An estimated US$335 million is needed for all necessary work on Pompeii.

AMALFI COAST.

The Costiera Amalfitana, a World Heritage Site, stretches about 50kms along the southern side of the Sorrento Peninsula. Cliffs terraced with lemon groves and pastel villas cling to unforgiving slopes. For centuries after Amafi’s glory days as a maritime power from the 9th to the 11th centuries, the area was poor and its isolated villages were victims of foreign incursions, earthquakes and landslides. That isolation drew the first visitors in the early 1900s that in the latter half of the century led to the tourist mecca it is today. The best time to visit is in late spring or early autumn as the summer is very busy and it shuts down in the winter.

Unlike Cinque Terre that can only really be visited on foot, the Amalfi coast can only really be seen with a vehicle. The road along the coast is a masterpiece of construction. The coast away from the towns is rugged cliff usually dropping vertically into the ocean. Much of the narrow two-lane, very twisty road is built using rock walls for support. Tunnels are rare until around Amalfi. Speeds rarely exceed 50km/hour and cars rarely have room for a safe pass. As Italians love to cut corners, extreme defensive driving is necessary. The road is made considerably narrower by all the cars parked along it, especially around Positano and the towns. Motorcycles come here for the drive – at the speeds traveled they can’t see much of the spectacular scenery. They seem to have a death wish claiming the road for themselves. Add bicycles (Sunday is a big day for cycling in Italy), the occasional pedestrian and busses and is can be a challenging drive. I can only imagine what it would be like in the busy summer months. Safe pull-offs to see the marvelous views are fairly common but are really only available to vehicles traveling east.

Tour boats are widely available to see the coast from the water.

Well before the coast, I hit a motorcyclist on the side of the road. He was parked, off his bike and stepped onto the road without looking. My right mirror struck him in the arm and twisted the mirror up into its folded position.

With all the tourists, living here must be a nightmare.

Walking the Coast. The steep, rugged and densely forested Lattari mountains provide stunning walking in a large network of paths. It’s tough going with long ascents up seemingly endless flights of steps. The best-known path is the 12km Sentiero degli Dei (Path of the Gods) linking Positano to Praiano. It’s a mountain-top trail punctuated by caves, terraces and deep valleys. Hiking maps can be downloaded at www.amalficoastweb.com.

POSITANO (pop 3900)

The coast’s most photogenic and expensive town, the steeply stacked houses are a medley of pastels and terracotta. Cars were parked on the highway for a few kilometres before and after the town. The streets are nearly vertical, usually staircases, and are lined with the usual tourist shops, hotels and restaurants, much with some crumbling stucco. The road is high above the town. From the first exit, many cars drive down a severe switchbacking road directly into the town. I stayed up on the highway that descends to just above the main town. But I was unable to park so missed seeing the church.

Chiesa di Santa Maria Assunta. With a colourful majolica-tiled dome, this is pretty much the only thing to see in Positano. The classic interior has pillars topped with gilded ionic capitals and cherubs above every arch. Above the altar is a 13th century Byzantine Black Madonna and Child.

Ceramiche d’Arte Carmela. This ceramics factory is right on the highway just past Positano. Even if it is not open, most of the product is displayed around the property: large jugs and round table tops connected by ropes line the terraced rock walls, planters, small, round and larger rectangular tables on wrought iron stands, chair seats, fish, tile compositions and a whole range of dishes. Hours are M-F 9-6 and Saturdays 9-1 pm, closed on Sundays. They have stores in most of the towns.

Praiano. This ancient fishing village has one of the coast’s most popular beaches. It is reached by a steep path down the side of the cliffs to a tiny inlet.

Marina di Furore sits at the bottom of a giant cleft that cuts through the mountains. It is tiny and attracts few tourists.

Grotta dello Smeraldo. Take an elevator 70m down the cliff to this cave on the water. The cave formations are mediocre at best – small stalactites and a few columns. The real draw is that it is at water level although not accessible from the sea. A rectangular rowboat waits for a full load and takes you on a mini-tour. I don’t think many had seen a good cave as they were all impressed and gave tips. €5

AMALFI (pop 5430). Once a maritime superpower with a population of 70,000, it is now a little village easily traversed in 20 minutes on foot. Because of an earthquake in 1343, most of the old city, and its populace, simply slid into the sea. Parking is near impossible and I did my usual highly illegal park to walk into the town that extends up the gorge. A large square has the usual tourist shops and restaurants.

Cathedral di Sant’Andrea. Off the square, climb 57 steps up to the church. The façade is two-toned green and white masonry and has wonderful mosaics. The huge bronze doors were made in Syria. The old church and its cloister with double columns date to the early 10th century and now serves as a museum. Take stairs down into the marble-wonder crypt and then climb up to the cathedral. The relatively austere interior is best appreciated from the back to see the gilt ceiling and marble inlay columns. €3

Museo della Carta. The paper museum is in a rugged, cave-like 13th-century paper mill with original paper presses still in working order. The original paper is cotton-based. See by guided tour (in Italian). A shop in town sells the cards, envelopes, fans and prints. €4

RAVELLO (pop 2500). This village is 7kms above Amalfi and reached by a sinuous road. I followed a bus up that was very efficient at clearing the road. There are stupendous views of the coast to the east.

Oscar Niemeyer Auditorium. With a curved roof (badly in need of repair), the façade is stunning black glass surrounded by the white curved roof-line. It is primarily a movie theatre. Free

Villa Rufolo. This is a 13th-century residence has a museum in the tower. Known for its gardens, they are probably not worth visiting before May. The flowers had just been planted. €7, €5 reduced

CASERTA

Located 40 kilometres (25 mi) north of Naples, it is an important agricultural, commercial and industrial city. Caserta is located on the edge of the Campanian plain at the foot of the Campanian Subapennine mountain range. The city is best known for the Palace of Caserta.

History. Modern Caserta was established around the defensive tower built in Lombard times by Pando, Prince of Capuad. Pando destroyed the original city around 863. The tower is now part of the Palazzo della Prefettura which was once the seat of the counts of Caserta, as well as a royal residence. The original population moved from Casertavecchia (former bishopric seat) to the current site in the 16th century. Casertavecchia was built on the Roman town of Casa Irta, meaning “home village located above” and later contracted as “Caserta”.

The city and vicinity were the property of the Acquaviva family who, being pressed by huge debts, sold all the land to the royal family. The royal family then selected Caserta for the construction of their new palace which, being inland, was seen as more defensible than the previous palace fronting the Bay of Naples.

At the end of World War II, the royal palace served as the seat of the Supreme Allied Commander. The first Allied war trial took place here in 1945; German general Anton Dostler was sentenced to death and executed nearby, in Aversa.

Pope Francis visited Caserta on Monday, 28 June 2014, together with a friend named Giovanni Traettino who pastors an evangelical, charismatic/Pentecostal Protestant church. The Pope apologized for the complicity of some Catholics in the persecution of Protestant Pentecostals during the fascist regime in Italy.

Royal Palace of Caserta (Reggia di Caserta). Caserta’s main attraction is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site). The royal palace (“Reggia”)was designed in the 18th century by the Italian architect Luigi Vanvitelli, recalling Versaillesd, as a residence for the Bourbon kings of Naples and Sicily.

As one of the most visited monuments in Italy, the palace has more than 1200 rooms, decorated in various styles. The park is 2 miles (3.2 km) long and contains many waterfalls, lakes and gardens, as well as a very famous English garden.

The World Heritage Sites consists of the 18th-Century Royal Palace at Caserta with the Park, the Aqueduct of Vanvitelli, and the San Leucio Complex

The Aqueduct of Vanvitelli or Caroline Aqueduct is an 1,736′ aqueduct built in 1762 to supply the Reggia di Caserta and the San Leucio complex, supplied by water arising at the foot of Taburno, from the springs of the Fizzo, in the territory of Bucciano, which it carries along a winding 38 km route. It is in the Valle di Maddaloni.