Overseas Visitors Pass. This pass gives free access to approximately 100 sites on the English Heritage List. It comes as either 9 days (54£ for two) or 16 days (64£ for two). Buy it online and activate it at any of the sites. There were few places around London to use it and I was doubting its worth, but with some determination, it is of great value. Stonehenge alone covers ⅔ of the cost.

April 4, 2018

It was a truly horrendous day when we visited Stonehenge, about 100 km west of London and just north of Salisbury. Cold and raining, the wind was so strong, an umbrella was impractical. Despite the weather, there were still lots of other tourists. I couldn’t imagine what it would be like in nice weather.

STONEHENGE

Stonehenge is a prehistoric monument in Wiltshire, England, 2 miles (3 km) west of Amesbury. The stones are set within earthworks in the middle of the densest complex of Neolithic and Bronze Age monuments in England, including several hundred burial mounds.

Archaeologists believe it was constructed from 3000 BC to 2000 BC. The surrounding circular earth bank and ditch, which constitute the earliest phase of the monument, have been dated to about 3100 BC. Radiocarbon dating suggests that the first bluestones were raised between 2400 and 2200 BC, although they may have been at the site as early as 3000 BC.

One of the most famous landmarks in the UK, Stonehenge is regarded as a British cultural icon. Stonehenge could have been a burial ground from its earliest beginnings. Deposits containing human bone date from as early as 3000 BC, when the ditch and bank were first dug, and continued for at least another five hundred years.

Etymology. Archaeologists define henges as earthworks consisting of a circular banked enclosure with an internal ditch. Because its bank is inside its ditch, Stonehenge is not truly a henge site.

Despite being contemporary with true Neolithic henges and stone circles, Stonehenge is in many ways atypical—for example, at more than 7.3 meters (24 ft) tall, its extant trilithons’ lintels, held in place with mortise and tenon joints, make it unique.

Early history. Stonehenge was a place of burial from its beginning to its zenith in the mid-third millennium B.C. Stonehenge evolved in several construction phases spanning at least 1500 years. There is evidence of large-scale construction on and around the monument that perhaps extends the landscape’s time frame to 6500 years.

Before the monument (8000 BC forward)

Archaeologists have found four, or possibly five, large Mesolithic postholes (one may have been a natural tree throw), which date to around 8000 BC, beneath the nearby modern tourist car park. These held pine posts around 0.75 meters (2 ft 6 in) in diameter, which were erected and eventually rotted in situ. Three of the posts were in an east-west alignment which may have had ritual significance. A settlement that may have been contemporaneous with the posts has been found at Blick Mead, a reliable year-round spring 1 mile (1.6 km) from Stonehenge.

Salisbury Plain was then still wooded, but 4,000 years later, during the earlier Neolithic, people built a causewayed enclosure at Robin Hood’s Ball and long barrow tombs in the surrounding landscape.

In approximately 3500 BC, a Stonehenge Cursus was built 700 meters (2,300 ft) north of the site as the first farmers began to clear the trees and develop the area. Several other adjacent stone and wooden structures and burial mounds, previously overlooked, may date as far back as 4000 BC.

Stonehenge 1 (ca. 3100 BC)

The first monument consisted of a circular bank and ditch enclosure made of Late Cretaceous (Santonian Age) Seaford Chalk, measuring about 110 meters (360 ft) in diameter, with a large entrance to the northeast and a smaller one to the south. It stood in open grassland on a slightly sloping spot. The builders placed the bones of deer and oxen in the bottom of the ditch, as well as some worked flint tools. The bones were considerably older than the antler picks used to dig the ditch, and the people who buried them had looked after them for some time before burial. The ditch was continuous but had been dug in sections, like the ditches of the earlier causewayed enclosures in the area. The chalk dug from the ditch was piled up to form the bank. This first stage is dated to around 3100 BC, after which the ditch began to silt up naturally.

Within the outer edge of the enclosed area is a circle of 56 pits, each about a meter in diameter, known as the Aubrey holes after John Aubrey, the seventeenth-century antiquarian who was thought to have first identified them. The pits may have contained standing timbers creating a timber circle, although there is no excavated evidence of them. A recent excavation has suggested that the Aubrey Holes may have originally been used to erect a bluestone circle. If this were the case, it would advance the earliest known stone structure at the monument by some 500 years. A small outer bank beyond the ditch could also date to this period.

In 2013 a team of archaeologists, led by Mike Parker Pearson, excavated more than 50,000 cremated bones of 63 individuals buried at Stonehenge. These remains had originally been buried individually in the Aubrey holes, exhumed during a previous excavation conducted by William Hawley in 1920, been considered unimportant by him, and subsequently re-interred together in one hole, Aubrey Hole 7, in 1935. Physical and chemical analysis of the remains has shown that the cremated were almost equally men and women and included some children. As there was evidence of the underlying chalk beneath the graves being crushed by the substantial weight, the team concluded that the first bluestones brought from Wales were probably used as grave markers. Radiocarbon dating of the remains has put the date of the site 500 years earlier than previously estimated, to around 3000 BC.

Stonehenge 2 (ca. 3000 BC)

Evidence of the second phase is no longer visible. The number of postholes dating to the early 3rd millennium BC suggests that some form of timber structure was built within the enclosure during this period. Further standing timbers were placed at the northeast entrance, and a parallel alignment of posts ran inwards from the southern entrance. The postholes are smaller than the Aubrey Holes, being only around 0.4 meters (16 in) in diameter, and are much less regularly spaced. The bank was purposely reduced in height and the ditch continued to silt up. At least twenty-five of the Aubrey Holes are known to have contained later, intrusive, cremation burials dating to the two centuries after the monument’s inception. It seems that whatever the holes’ initial function, it changed to become a funerary one during Phase 2. Thirty further cremations were placed in the enclosure’s ditch and at other points within the monument, mostly in the eastern half. Stonehenge is therefore interpreted as functioning as an enclosed cremation cemetery at this time, the earliest known cremation cemetery in the British Isles. Fragments of unburnt human bone have also been found in the ditch-fill. Dating evidence is provided by the late Neolithic grooved ware pottery that has been found in connection with the features from this phase.

Stonehenge 3 I (ca. 2600 BC)

Archaeological excavation has indicated that around 2600 BC, the builders abandoned timber in favour of stone and dug two concentric arrays of holes (the Q and R Holes) in the center of the site. These stone sockets are only partly known however, they could be the remains of a double ring. Again, there is little firm dating evidence for this phase. The holes held up to 80 standing stones (shown blue on the plan), only 43 of which can be traced today. It is generally accepted that the bluestones (some of which are made of dolerite, an igneous rock), were transported by the builders from the Preseli Hills, 150 miles (240 km) away in modern-day Pembrokeshire in Wales.

The long-distance human transport theory was bolstered in 2011 by the discovery of a megalithic bluestone quarry at Craig Rhos-y-Felin, near Crymych in Pembrokeshire, which is the most likely place for some of the stones to have been obtained. Other standing stones may well have been small sarsens (sandstone), used later as lintels.

The stones, which weighed about two tons, could have been moved by lifting and carrying them on rows of poles and rectangular frameworks of poles, as recorded in China, Japan, and India. It is not known whether the stones were taken directly from their quarries to Salisbury Plain or were the result of the removal of a venerated stone circle from Preseli to Salisbury Plain to “merge two sacred centers into one, to unify two politically separate regions, or to legitimize the ancestral identity of migrants moving from one region to another”.

Each monolith measures around 2 meters (6.6 ft) in height, between 1 and 1.5 m wide and around 0.8 meters thick. What was to become known as the Altar Stone is almost certainly derived from the Senni Beds, perhaps from 50 miles (80 kilometres) east of Mynydd Preseli in the Brecon Beacons.

The north-eastern entrance was widened at this time, with the result that it precisely matched the direction of the midsummer sunrise and midwinter sunset of the period. This phase of the monument was abandoned unfinished, however; the small standing stones were removed and the Q and R holes purposefully backfilled. Even so, the monument appears to have eclipsed the site at Avebury in importance towards the end of this phase.

The Heelstone, a Tertiary sandstone, may also have been erected outside the north-eastern entrance during this period. It cannot be accurately dated and may have been installed at any time during phase 3. At first, it was accompanied by a second stone, which is no longer visible. Two, or possibly three, large portal stones were set up just inside the northeastern entrance, of which only one, the fallen Slaughter Stone, 4.9 meters (16 ft) long, now remains.

Other features, loosely dated to phase 3, include the four Station Stones, two of which stood atop mounds. The mounds are known as “barrows” although they do not contain burials. Stonehenge Avenue, a parallel pair of ditches and banks leading 2 miles (3 km) to the River Avon, was also added. Two ditches similar to the Heelstone Ditch circling the Heelstone (which was by then reduced to a single monolith) were later dug around the Station Stones.

Stonehenge 3 II (2600 BC to 2400 BC)

During the next major phase of activity, 30 enormous Oligocene-Miocene sarsen stones were brought to the site. They may have come from a quarry around 25 miles (40 km) north of Stonehenge on the Marlborough Downs. The stones were dressed and fashioned with mortise and tenon joints before 30 were erected as a 33-meter (108 ft) diameter circle of standing stones, with a ring of 30 lintel stones resting on top. The lintels were fitted to one another using another woodworking method, the tongue, and groove joint. Each standing stone was around 4.1 meters (13 ft) high, 2.1 meters (6 ft 11 in) wide, and weighed around 25 tons. Each had been worked with the final visual effect in mind; the orthostats widen slightly towards the top so that their perspective remains constant when viewed from the ground, while the lintel stones curve slightly to continue the circular appearance of the earlier monument.

The inward-facing surfaces of the stones are smoother and more finely worked than the outer surfaces. The average thickness of the stones is 1.1 meters and the average distance between them is 1 meter. A total of 75 stones would have been needed to complete the circle (60 stones) and the trilithon horseshoe (15 stones). It was thought the ring might have been left incomplete, but an exceptionally dry summer in 2013 revealed patches of parched grass that may correspond to the location of removed sarsens. The lintel stones are each around 3.2 meters long, 1 meter wide, and 0.8 meters thick. The tops of the lintels are 4.9 meters (16 ft) above the ground.

Within this circle stood five trilithons of dressed sarsen stone arranged in a horseshoe shape 13.7 meters (45 ft) across, with its open end facing northeast. These huge stones, ten uprights, and five lintels weigh up to 50 tons each. They were linked using complex jointing. They are arranged symmetrically. The smallest pair of trilithons were around 6 meters (20 ft) tall, the next pair a little higher, and the largest, single trilithon in the southwest corner would have been 7.3 meters (24 ft) tall. Only one upright from the Great Trilithon still stands, of which 6.7 meters (22 ft) is visible and a further 2.4 meters (7 ft 10 in) is below ground. The images of a ‘dagger’ and 14 ‘axeheads’ have been carved on one of the sarsens, known as stone 53; further carvings of axeheads have been seen on the outer faces of stones 3, 4, and 5. The carvings are difficult to date but are morphologically similar to late Bronze Age weapons. Early 21st-century laser scanning of the carvings supports this interpretation.

This ambitious phase has been radiocarbon dated to between 2600 and 2400 BC, slightly earlier than the Stonehenge Archer, discovered in the outer ditch of the monument in 1978, and the two sets of burials, known as the Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen, discovered 5 km to the west. Analysis of animal teeth found 3 km away at Durrington Walls, thought to be the ‘builders camp’, suggests that, during some period between 2600 and 2400 BC, as many as 4,000 people gathered at the site for the mid-winter and mid-summer festivals; the evidence showed that the animals had been slaughtered around 9 months or 15 months after their spring birth. Strontium isotope analysis of the animal teeth showed that some had been brought from as far afield as the Scottish Highlands for the celebrations. At about the same time, a large timber circle and a second avenue were constructed at Durrington Walls overlooking the River Avon. The timber circle was oriented towards the rising sun on the midwinter solstice, opposing the solar alignments at Stonehenge. The avenue was aligned with the setting sun on the summer solstice and led from the river to the timber circle. Evidence of huge fires on the banks of the Avon between the two avenues also suggests that both circles were linked. They were perhaps used as a procession route on the longest and shortest days of the year. Parker Pearson speculates that the wooden circle at Durrington Walls was the center of a ‘land of the living, whilst the stone circle represented a ‘land of the dead, with the Avon serving as a journey between the two.

Stonehenge 3 III (2400 BC to 2280 BC)

Later in the Bronze Age, although the exact details of activities during this period are still unclear, the bluestones appear to have been re-erected. They were placed within the outer sarsen circle and may have been trimmed in some way. Like the sarsens, a few have timber-working style cuts in them suggesting that, during this phase, they may have been linked with lintels and were part of a larger structure.

Stonehenge 3 IV (2280 BC to 1930 BC)

This phase saw further rearrangement of the bluestones. They were arranged in a circle between the two rings of sarsens and in an oval at the center of the inner ring. Some archaeologists argue that some of these bluestones were from a second group brought from Wales. All the stones formed well-spaced uprights without any of the linking lintels inferred in Stonehenge 3 III. The Altar Stone may have been moved within the oval at this time and re-erected vertically. Although this would seem the most impressive phase of work, Stonehenge 3 IV was rather shabbily built compared to its immediate predecessors, as the newly re-installed bluestones were not well-founded and began to fall over. However, only minor changes were made after this phase.

Stonehenge 3 V (1930 BC to 1600 BC)

Soon afterward, the northeastern section of the Phase 3 IV bluestone circle was removed, creating a horseshoe-shaped setting (the Bluestone Horseshoe) which mirrored the shape of the central sarsen Trilithons. This phase is contemporary with the Seahenge site in Norfolk.

After the monument (1600 BC on)

The Y and Z Holes are the last known construction at Stonehenge, built about 1600 BC, and the last usage of it was probably during the Iron Age. Roman coins and medieval artifacts have all been found in or around the monument but it is unknown if the monument was in continuous use throughout British prehistory and beyond, or exactly how it would have been used. Notable is the massive Iron Age hillfort Vespasian’s Camp built alongside the Avenue near the Avon. A decapitated seventh-century Saxon man was excavated from Stonehenge in 1923. The site was known to scholars during the Middle Ages and since then it has been studied and adopted by numerous groups.

Function and construction – Theories about Stonehenge

Stonehenge was produced by a culture that left no written records. Many aspects of Stonehenge, such as how it was built and which purposes it was used for, remain subject to debate. Several myths surround the stones.

The site, specifically the great trilithon, the encompassing horseshoe arrangement of the five central trilithons, the heel stone, and the embanked avenue, are aligned to the sunset of the winter solstice and the opposing sunrise of the summer solstice. A natural landform at the monument’s location followed this line and may have inspired its construction. The excavated remains of culled animal bones suggest that people may have gathered at the site for the winter rather than the summer. Further astronomical associations, and the precise astronomical significance of the site for its people, are a matter of speculation and debate.

There is little or no direct evidence revealing the construction techniques used by the Stonehenge builders. Over the years, various authors have suggested that supernatural or anachronistic methods were used, usually asserting that the stones were impossible to move otherwise due to their massive size. However, conventional techniques, using Neolithic technology as basic as shear legs, have been demonstrably effective at moving and placing stones of a similar size.

How the stones could be transported by prehistoric people without the aid of the wheel or a pulley system is not known. The most common theory of how prehistoric people moved megaliths has them creating a track of logs on which the large stones were rolled along. Another megalith transport theory involves the use of a type of sleigh running on a track greased with animal fat. Such an experiment with a sleigh carrying a 40-ton slab of stone was successful near Stonehenge in 1995. A dedicated team of more than 100 workers managed to push and pull the slab along the 18-mile (29 km) journey from Marlborough Downs. Proposed functions for the site include usage as an astronomical observatory or as a religious site.

More recently two major new theories have been proposed. It has been suggested that Stonehenge was a place of healing—the primeval equivalent of Lourdes. They argue that this accounts for the high number of burials in the area and for the evidence of trauma deformity in some of the graves. However, they do concede that the site was probably multifunctional and used for ancestor worship as well. Isotope analysis indicates that some of the buried individuals were from other regions. A teenage boy buried approximately 1550 BC was raised near the Mediterranean Sea; a metal worker from 2300 BC dubbed the “Amesbury Archer” grew up near the alpine foothills of Germany; and the “Boscombe Bowmen” probably arrived from Wales or Brittany, France.

On the other hand, Mike Parker Pearson of Sheffield University has suggested that Stonehenge was part of a ritual landscape and was joined to Durrington Walls by their corresponding avenues and the River Avon. He suggests that the area around Durrington Walls Henge was a place of the living, whilst Stonehenge was a domain of the dead. A journey along the Avon to reach Stonehenge was part of a ritual passage from life to death, to celebrate past ancestors and the recently deceased.

Both explanations were first mooted in the twelfth century by Geoffrey of Monmouth, who extolled the curative properties of the stones and was also the first to advance the idea that Stonehenge was constructed as a funerary monument. Whatever religious, mystical, or spiritual elements were central to Stonehenge, its design includes a celestial observatory function, which might have allowed the prediction of eclipse, solstice, equinox, and other celestial events important to a contemporary religion.

There are other hypotheses and theories. According to a team of British researchers led by Mike Parker Pearson of the University of Sheffield, Stonehenge may have been built as a symbol of “peace and unity”, indicated in part by the fact that at the time of its construction, Britain’s Neolithic people were experiencing a period of cultural unification.

Researchers from the Royal College of Art in London have discovered that the monument’s bluestones possess “unusual acoustic properties” — when struck they respond with a “loud clanging noise”. According to Paul Devereux, editor of the journal Time and Mind: The Journal of Archaeology, Consciousness, and Culture, this idea could explain why certain bluestones were hauled nearly 200 miles (320 km)—a major technical accomplishment at the time. In certain ancient cultures rocks that ring out, known as lithophones, were believed to contain mystic or healing powers, and Stonehenge has a history of association with rituals. The presence of these “ringing rocks” seems to support the hypothesis that Stonehenge was a “place for healing”. The bluestones of Stonehenge were quarried near a town in Wales called Maenclochog, which means “ringing rock”, where the local bluestones were used as church bells until the 18th century.

Modern history

“Heel Stone“, “Friar’s Heel”, or “Sun-Stone”. The Heel Stone lies northeast of the sarsen circle, beside the end portion of Stonehenge Avenue. It is a rough stone, 16 feet (4.9 m) above ground, leaning inwards towards the stone circle. It has been known by many names in the past, including “Friar’s Heel” and “Sun-stone”. At summer solstice an observer standing within the stone circle, looking northeast through the entrance, would see the Sunrise in the approximate direction of the heel stone, and the sun has often been photographed over it.

Stonehenge has changed ownership several times since King Henry VIII acquired Amesbury Abbey and its surrounding lands. In 1540 Henry gave the estate to the Earl of Hertford. It subsequently passed to Lord Carleton and then the Marquess of Queensberry. The Antrobus family of Cheshire bought the estate in 1824. During World War I an aerodrome (Royal Flying Corps “No. 1 School of Aerial Navigation and Bomb Dropping”) was built on the downs just to the west of the circle and, in the dry valley at Stonehenge Bottom, the main road junction was built, along with several cottages and a cafe. The Antrobus family sold the site after their last heir was killed in the fighting in France. The auction by Knight Frank & Rutley estate agents in Salisbury was held on 21 September 1915 and included “Lot 15. Stonehenge with about 30 acres, 2 rods, 37 perches [12.44 ha] of adjoining downland.”

Cecil Chubb bought the site for £6,600 and gave it to the nation three years later. Although it has been speculated that he purchased it at the suggestion of—or even as a present for—his wife but he bought it on a whim, as he believed a local man should be the new owner.

In the late 1920s, a nationwide appeal was launched to save Stonehenge from the encroachment of the modern buildings that had begun to rise around it. By 1928 the land around the monument had been purchased with the appeal donations and given to the National Trust to preserve. The buildings were removed (although the roads were not), and the land returned to agriculture. More recently the land has been part of a grassland reversion scheme, returning the surrounding fields to native chalk grassland.

Neopaganism. During the twentieth century, Stonehenge began to revive as a place of religious significance, this time by adherents of Neopaganism and New Age beliefs, particularly the Neo-druids. The historian Ronald Hutton would later remark that “it was a great, and potentially uncomfortable, irony that modern Druids had arrived at Stonehenge just as archaeologists were evicting the ancient Druids from it.”

The first such Neo-druidic group to make use of the megalithic monument was the Ancient Order of Druids, who performed a mass initiation ceremony there in August 1905, in which they admitted 259 new members into their organization. This assembly was largely ridiculed in the press, which mocked the fact that the Neo-druids were dressed up in costumes consisting of white robes and fake beards.

Between 1972 and 1984, Stonehenge was the site of the Stonehenge Free Festival. After the Battle of the Beanfield in 1985, this use of the site was stopped for several years and ritual use of Stonehenge is now heavily restricted. Some Druids have arranged an assembling of monuments styled on Stonehenge in other parts of the world as a form of Druidism worship.

Setting and Access. When Stonehenge was first opened to the public it was possible to walk among and even climb on the stones, but the stones were roped off in 1977 as a result of serious erosion. Visitors are no longer permitted to touch the stones but can walk around the monument from a short distance away. English Heritage does, however, permit access during the summer and winter solstice, and the spring and autumn equinox. Additionally, visitors can make special bookings to access the stones throughout the year.

The access situation and the proximity of the two roads have drawn widespread criticism, highlighted by a 2006 National Geographic survey. In the survey of conditions at 94 leading World Heritage Sites, 400 conservation and tourism experts ranked Stonehenge 75th in the list of destinations, declaring it to be “in moderate trouble”.

As motorized traffic increased, the setting of the monument began to be affected by the proximity of the two roads on either side—the A344 to Shrewton on the north side, and the A303 to Winterbourne Stoke to the south. Plans to upgrade the A303 and close the A344 to restore the vista from the stones have been considered since the monument became a World Heritage Site. However, the controversy surrounding the expensive re-routing of the roads has led to the scheme being cancelled on multiple occasions. On 6 December 2007, it was announced that extensive plans to build a Stonehenge road tunnel under the landscape and create a permanent visitors’ center had been cancelled.

On 13 May 2009, the government approved a £25 million scheme to create a smaller visitors’ center and close the A344, although this was dependent on funding and local authority planning consent. On 20 January 2010 Wiltshire Council granted planning permission for a center 2.4 km (1.5 miles) to the west and English Heritage confirmed that funds to build it would be available, supported by a £10m grant from the Heritage Lottery Fund. On 23 June 2013, the A344 was closed to begin the work of removing the section of the road and replacing it with grass. The center, designed by Denton Corker Marshall, opened to the public on 18 December 2013.

Stonehenge Roundtable Access. The earlier rituals were augmented by the Stonehenge Free Festival, loosely organized by the Politantric Circle, held between 1972 and 1984, during which time the number of midsummer visitors had risen to around 30,000. However, in 1985 the site was closed to festivalgoers by English Heritage and the National Trust. A consequence of the end of the festival in 1985 was the violent confrontation between the police and New Age travellers that became known as the Battle of the Beanfield when police blockaded a convoy of travellers to prevent them from approaching Stonehenge. Beginning in 1985, the year of the Battle, no access was allowed into the stones at Stonehenge for any religious reason. This ‘exclusion zone policy continued for almost fifteen years: until just before the arrival of the twenty-first century, visitors were not allowed to go into the stones at times of religious significance, the winter and summer solstices, and the vernal and autumnal equinoxes.

However, now due to the Roundtable process and the ‘Court of Human Rights’ rulings gained by picketing by campaigners such as Brian “Viziondanz” Felstein and King Arthur Pendragon, some access has been gained four times a year. The ‘Court of Human Rights rulings recognize that members of any genuine religion have a right to worship in their own church, and Stonehenge is a place of worship for Neo-Druids, Pagans, and other Earth-based’ or ‘old’ religions. The Roundtable meetings include members of the Wiltshire Police force, National Trust, English Heritage, Pagans, Druids, Spiritualists, and others.

At the Summer Solstice 2003, which fell over a weekend, over 30,000 people attended a gathering at and in the stones. The 2004 gathering was smaller (around 21,000 people).

Archaeological research and restoration

1900–2000. William Gowland oversaw the first major restoration of the monument in 1901 which involved the straightening and concrete setting of sarsen stone number 56 which was in danger of falling. In straightening the stone he moved it about half a meter from its original position. Gowland also took the opportunity to further excavate the monument in what was the most scientific dig to date, revealing more about the erection of the stones than the previous 100 years of work had done. During the 1920 restoration, William Hawley excavated the base of six stones and the outer ditch. He also located a bottle of port in the Slaughter Stone socket left by Cunnington, helped to rediscover Aubrey’s pits inside the bank, and located the concentric circular holes outside the Sarsen Circle called the Y and Z Holes.

Richard Atkinson, Stuart Piggott, and John F. S. Stone re-excavated much of Hawley’s work in the 1940s and 1950s and discovered the carved axes and daggers on the Sarsen Stones. Atkinson’s work was instrumental in furthering the understanding of the three major phases of the monument’s construction.

In 1958 the stones were restored when three of the standing sarsens were re-erected and set in concrete bases. The last restoration was carried out in 1963 after stone 23 of the Sarsen Circle fell over. It was again re-erected, and the opportunity was taken to concrete three more stones.

In 1966 and 1967, in advance of a new car park being built at the site, the area of land immediately northwest of the stones was excavated by Faith and Lance Vatcher. They discovered the Mesolithic postholes dating from between 7000 and 8000 BC, as well as a 10-meter (33 ft) length of a palisade ditch – a V-cut ditch into which timber posts had been inserted that remained there until they rotted away. Subsequent aerial archaeology suggests that this ditch runs from the west to the north of Stonehenge, near the avenue.

Excavations were once again carried out in 1978 by Atkinson and John Evans during which they discovered the remains of the Stonehenge Archer in the outer ditch, and in 1979 rescue archaeology was needed alongside the Heel Stone after a cable-laying ditch was mistakenly dug on the roadside, revealing a new stone hole next to the Heel Stone.

In the early 1980s, Julian Richards led the Stonehenge Environs Project, a detailed study of the surrounding landscape. The project was able to successfully date such features as the Lesser Cursus, Coneybury Henge, and several other smaller features.

On 18 December 2011, geologists from the University of Leicester and the National Museum of Wales announced the discovery of the exact source of some of the rhyolite fragments found in the Stonehenge debitage. These fragments do not seem to match any of the standing stones or bluestone stumps. The researchers have identified the source as a 70-meter (230 ft) long rock outcrop called Craig Rhos-y-Felin (51°59′30.07″N 4°44′40.85″W), near Pont Saeson in north Pembrokeshire, located 220 kilometres (140 mi) from Stonehenge.

WILTSHIRE HERITAGE MUSEUM

This small museum in Devizes, about 20kms north of Stonehenge is well done. It has two significant exhibits. It has one of 3 original ‘shillings’ dating to Anglo-Saxon times. Gold, it cost the museum 21,000£ to purchase.

The second is the gravesite of the ‘Archer’ excavated at Stonehenge. It contained a wonderful gold belt buckle and a gold lozenge with a nice design – worth the price of admission alone. 5.5£ reduced to 2.75£ with the English Heritage pass.

AVEBURY.

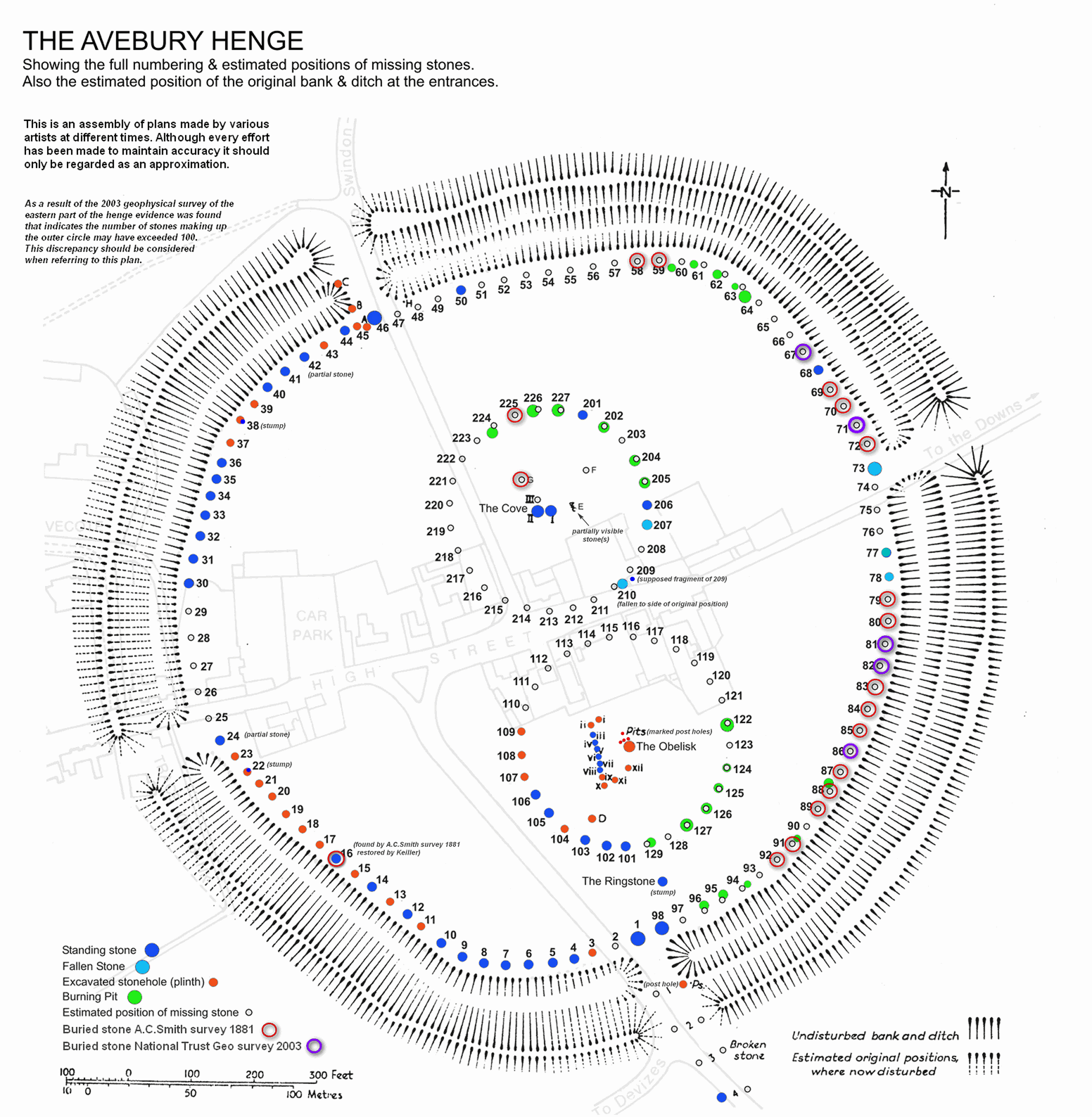

With a diameter of 348m, Avebury is the largest stone circle in the world. It’s also one of the oldest datings from 2500 to 2200 BC. Today more than 30 stones are in place; pillars show where missing stones would have been. A large section of the village is actually inside the stones and modern roads divide the circle into four sectors with footpaths winding around them. The SW sector has 11 standing stones including the Barber Surgeon Stone and the southeast starts with huge portal stones. In the northern inner circle remain three sarcens of what would have been a rectangular cove. The northwest sector has the most complete collection of standing stones including the massive 65-ton Swindon Stone, one of the few to have never been toppled.

Avebury henge originally consisted of an outer circle of 98 standing stones of up to 6m in length, many weighing 20 tons. The stones were surrounded by another circle delineated by a 5m-high earth bank and ditch up to 9m deep. Inside were smaller stone circles to the north (27 stones) and south (29 stones).

In the Middle Ages, when Britain’s pagan past was an embarrassment to the church, many of the stones were buried, removed or broken up. In 1934, the stones were re-erected and the site was purchased for posterity by the Keiller marmalade fortune.

Around Avebury are several other prehistoric sites.

Silbury Hill is a 40m high hill just south and is the largest artificial earthwork in Europe, comparable in height and volume to the Egyptian pyramids. It was built in stages from about 2500 BC but the precise reason is unclear. Direct access is not allowed and it can be viewed from a lay-by on A4.

West Kennet Long Barrow. This is England’s finest burial mound. Dating from 3500 BC, its entrance is guarded by huge sarsens and the roof is made of gigantic overlapping capstones. About 50 skeletons were found when it was excavated now in the Wiltshire Heritage Museum. A footpath leads 2 miles from Avebury to the barrow passing Silbury Hill on the way.